Profile

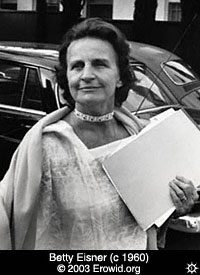

Betty Eisner

Birth:

1915

Death:

2004

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of California, Los Angeles (1956)

BA, Stanford University (1937)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Sequoia Seminar (1946-1958)

Brentwood Veteran’s Administration Hospital (1956-1959)

Association for Psycholytic Therapists (1961)

Albert Hofmann Foundation (1988-1990s)

Other Media:

Media Links

Archival Collections

Career Focus:

Psycholytic therapy, psychedelics, group therapy, clinical psychology, therapeutic communities, Human Potential Movement, bodywork, psychoanalysis

Biography

Betty Eisner was born Helen Elizabeth Grover on September 29, 1915 in Kansas City, Missouri. She graduated high school in 1933 and promptly left Missouri for Stanford University, where she enrolled in a political science undergraduate program. A tenacious student, Eisner was awarded numerous scholarships, was actively involved in campus politics, and was mentored by notable professors such as psychologist Lewis Terman and legal scholar Harry Rathbun. Eisner graduated with a BA in 1937. That same year, she married Stanford mechanical engineering student Willard Eisner and the two moved to Santa Monica, where Willard found employment with the RAND Corporation, a think tank founded immediately after WWII to provide research and analysis to U.S. military planning.

In the years following her graduation, Eisner took an interest in mysticism, meditation, and unconscious exploration. She studied spiritual and psychological practices at California retreat centres such as Jiddu Krishnamurti’s Arya Vihara, Gerald Heard’s Trabuco College, and the Sequoia Seminar, an annual summer gospel study retreat in the San Francisco Bay Area led by Harry Rathbun and his wife, Emilia. The Sequoia Seminar was an especially influential site for Eisner. Founded by the Rathbuns in 1946, the Seminar was focused on modernized readings of the bible as a text about the psychology of moral leadership and the fulfillment of personal potential. In addition to the gospels, Seminarians read psychological theories of creativity, individuation, and mystical experiences. The Sequoia Seminar thus exposed Eisner to a spiritual model of depth psychology that was explored in a group format.

Eisner attended the Sequoia Seminar annually. In 1951, she applied to study clinical psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), citing the influence of a Seminar session on Rorschach therapy. She was accepted to study under the supervision of Bruno Klopfer, founder of the Rorschach Institute and a major proponent of Jungian analytic psychology. For her dissertation, Eisner administered Rorschach tests to women who experienced infertility with no discernible organic cause, with the intention of finding unconscious origins for their infertility. To learn clinical practice, Eisner applied for an internship at a Veterans’ Administration (VA) psychiatric hospital. However, her application was nearly rejected on the basis that UCLA did not permit women to intern at VA hospitals, much less a married woman with one young child and the possibility of having more (Eisner and her husband had their first child, a daughter, in 1952). Eisner’s department had preferred she intern with UCLA’s child clinic or student health centre, depriving her of the chance to study applications of psychotherapy to psychosis and other acute psychiatric diagnoses. To rectify this, Eisner confronted her administration tirelessly, threatening to take her complaints of discrimination to the public if the policy was not changed. She succeeded in circumventing the ban and graduated with a PhD in clinical psychology in 1956.

While finishing her dissertation, Eisner came across a bulletin for a graduate research assistant position in an experimental drug study. She had a hunch that drug was LSD, a new hallucinogen from Switzerland that had just begun making inroads into American psychiatry in the early 1950s. She had just heard of the drug at a recent Sequoia Seminar workshop facilitated by British philosopher Gerald Heard, who spoke of its ability to produce mystical experiences. Too busy working on her dissertation to apply for the position, Eisner nonetheless contacted the study director Sidney Cohen to volunteer as a participant. In November of 1955, Eisner arrived at the Brentwood VA Hospital to take a 100ug dose of LSD and submit to an evaluation of her “ego functioning.” Cohen administered then-common assessment instruments such as the TAT and MMPI. Eisner found the tasks to be tedious distractions from the LSD experience, which otherwise pulled her toward deep psychological and spiritual insights. Though the experiment used LSD to explore the structure of the mind, participation in the study had given Eisner a feel for the drug’s therapeutic potential.

Eisner’s participation in the study had a remarkable impact on her life. Inspired to work with LSD as a clinician, Eisner maintained regular communication with Cohen until her graduation, after which Cohen hired her to co-investigate the therapeutic properties of LSD at the Brentwood VA Hospital. Between 1956 and 1959, Eisner and Cohen were primary collaborators, co-authoring numerous studies on LSD’s clinical applications. Their research received widespread attention primarily for two features. One was their use of low doses of LSD that were gradually increased over many sessions. Until that time, most LSD studies had used high doses of the drug to investigate states that resembled psychosis. Contrarily, Cohen and Eisner started patients on 25ug, because they noticed that low doses kept patients grounded enough to communicate clearly with the therapist, but affected enough to form novel associations, engage in more free-flowing honesty about their internal experience, and recall long-repressed trauma. The other unique dimension to their work was their codification of the “integrative experience.” Characteristics of an integrative experience included a sense of peace with one’s life conditions, a cathartic release of a trauma’s emotional burden, and a deep, spiritual feeling of one’s interconnectedness with the world. The reliability with which LSD produced integrative experiences led Eisner and Cohen to the conclusion that the drug dismantled ego defenses, which opened up space for catharsis and healing. By the early 1960s, Eisner and other practitioners who employed low doses of LSD in psychodynamic therapy consolidated the model under the term “psycholytic therapy.”

Eisner was a passionate proponent of psycholytic therapy. She was an active member of the psychedelic psychiatry community, presenting at conferences in the United States and Europe and forming close relationships with important figures in the field such as Humphrey Osmond and Ronald Sandison. In 1961, Eisner participated in the formation of the Association for Psycholytic Therapy (APT), an organization that counted her among the “founding fathers” of psycholytic therapy. Her inclusion as a founder was not without debate. Europe was home to most of the world’s psycholytic therapists, but the European practitioners were mainly psychiatrists who resisted the notion of a psychologist providing drug treatment. Despite its appearance as a professional disagreement, the marginalization of psychologists was also highly gendered, as many more women were psychologists than psychiatrists at the time. This was not lost on Eisner, who confided to a colleague her suspicion that the APT sought to exclude her based on her gender. Nonetheless, Eisner was able to argue her point that her experience practicing, researching, and representing psycholytic therapy at conferences warranted her inclusion as a founder of the field.

In her private practice, Eisner experimented with a multitude of methods for producing psycholytic states besides LSD. These methods included Ritalin, carbogen (a mixture of 70% oxygen and 30% carbon dioxide), and in later years, ketamine, bodywork, and hydrotherapy. These experiments came partly because of growing restrictions against the experimental and therapeutic use of LSD. Until the early 1960s, LSD was relatively easily available to health practitioners affiliated with hospitals or research programs. As the drug became increasingly available to the public and eventually took on an emblematic role in the 1960s counterculture, its manufacturer’s distribution policies became more stringent. By 1969, the United States outlawed all uses of LSD. Additionally, Eisner’s relationship with the psychedelic psychotherapy community was fracturing; it was more difficult to collaborate with her European colleagues than she had anticipated, and soon the APT petered out, only to reappear in 1964 as the psychiatry-focused European Medical Society of Psycholytic Therapy (EPT).

Eisner adapted to the limitations imposed on LSD work. Between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s, Eisner focused on developing her group therapy practice. Group therapy with Eisner involved many of the techniques associated with the humanistic, gestalt, and transpersonal therapies of the countercultural era. Clients participated in encounter groups, some of which lasted through the night. They often involved the administration of psycholytic substances; LSD in the beginning, and later Ritalin and Ketamine. Eisner facilitated the group through somatic activities and relational encounters designed to dismantle clients’ ego defences and put them in touch with their primary emotions and repressed memories. She also achieved this using nonverbal methods such as hot mineral baths and a form of massage called “Rolfing.” These methods often facilitated emotional releases and memory relivings that Eisner attributed not only to repressed personal memory, but also past-life memory. Eisner’s intention was to establish not just a group therapy practice, but a therapeutic community of clients who lived together and incorporated psychospiritual healing into every aspect of their social lives. At its height, Eisner’s community had more than forty members living in houses and apartments that Eisner’s family owned in the Santa Monica area.

Although Eisner’s practices and explanations contravened the evidentiary and client-therapist boundary conventions of clinical psychology, they were part of a trend toward spirituality and radical authenticity that came to be identified as transpersonal psychology. Nonetheless, Eisner’s proclivity for therapeutic practices that challenged convention and reached for spiritual and supernatural explanations eventually got her into deep trouble that culminated in the loss of her clinical license. In 1976, one of Eisner’s clients died under treatment that involved a mineral bath, Rolfing and Ritalin ingestion. Following this event, the California Board of Medical Quality Assurance (BMQA) conducted a wrongful death investigation against Eisner. They obtained affidavits from clients that revealed a host of concerning accusations: Eisner was purported to charge clients for mandatory sessions, deter them from seeking medical attention for injuries garnered during ketamine and Rolfing sessions, give them LSD under the guise of a different drug, and subject them to physically and emotionally harmful treatments against their wills. Additionally, the BMQA’s expert witnesses reprimanded Eisner for her use of treatments that had no basis in scientific evidence and her lack of adherence to drug safety protocols. In 1978, the BMQA revoked Eisner’s license to practice psychology.

Eisner tried to reinstate her license in the 1980s to no avail. Instead, she reestablished her connection to the psychedelic research community through organizational work. In 1988, the Albert Hofmann Foundation was launched in honour of Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who first synthesized LSD. The non-profit foundation was dedicated to preserving the history of psychedelic science. Eisner was a director and advisor of the foundation, sitting alongside former colleagues and important figures in psychedelic history such as Abram Hoffer, Myron Stolaroff, Oscar Janiger, Ram Dass, and Rick Doblin. Her tasks included planning conferences and events, including the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of LSD’s origins in 1994. In 2001, Eisner donated volumes of personal and professional documents to the Stanford University Library Archives. In 2002, she wrote a memoir of her professional life. Titled Remembrances of LSD Therapy Past, the memoir was not published, but is freely available online. Eisner passed away July 1st, 2004, in Santa Monica, California.

By Tal Davidson (2020)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Betty Eisner

Cohen, S., & Eisner, B. G. (1959). Use of lysergic acid diethylamide in a psychotherapeutic setting. AMA Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry, 81(5), 615-619.

Eisner, B. G. (1963). The influence of LSD on unconscious activity. In R. Crocket, R. Sandison & A. Walk, (Eds.), Hallucinogenic drugs and their psychotherapeutic use: The proceedings of the quarterly meeting of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association in London, February 1961 (141-145). London: HK Lewis & Co.

Eisner, B. G. (1964). Notes on the use of drugs to facilitate group psychotherapy. Psychiatric Quarterly, 38(1), 310-328.

Eisner, B. G. (1967). The importance of the non-verbal. In H.A. Abramson (Ed.), The use of LSD in psychotherapy and alcoholism (542 – 560). Indianapolis: The Bobb-Merrill Company.

Eisner, B. G. (1997). Bodywork and psychological healing. Journal of mind-body health, 13(3), 64-66.

Eisner, B. G. (2002). Remembrances of LSD therapy past. Retrieved from http://www.erowid.org/culture/characters/eisner_betty/remembrances_lsd_therapy. pdf.

Eisner, B. G. (2005). The birth and death of psychedelic therapy. In Walsh, R. Grob, C.S. (Eds.), Higher wisdom: Eminent elders explore the continuing impact of psychedelics (91-101). Albany: State University of New York.

About Betty Eisner

Gelber, S. M., & Cook, M. L. (1990). Saving the Earth: The history of a middle-class millenarian movement. Berkeley: University of California.

Novak, S. (1997). LSD before Leary: Sidney Cohen's Critique of 1950s Psychedelic Drug Research. Isis, 88(1), 87-110.

Davidson, T. (2017). The past lives of Betty Eisner: Examining the spiritual psyche of early psychedelic therapy through the story of an outsider, a pioneer, and a villain. [Master's thesis, York University]. YorkSpace Institutional Repository.

Photo Gallery

Betty Eisner

Birth:

1915

Death:

2004

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of California, Los Angeles (1956)

BA, Stanford University (1937)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Sequoia Seminar (1946-1958)

Brentwood Veteran’s Administration Hospital (1956-1959)

Association for Psycholytic Therapists (1961)

Albert Hofmann Foundation (1988-1990s)

Other Media:

Media Links

Archival Collections

Career Focus:

Psycholytic therapy, psychedelics, group therapy, clinical psychology, therapeutic communities, Human Potential Movement, bodywork, psychoanalysis

Biography

Betty Eisner was born Helen Elizabeth Grover on September 29, 1915 in Kansas City, Missouri. She graduated high school in 1933 and promptly left Missouri for Stanford University, where she enrolled in a political science undergraduate program. A tenacious student, Eisner was awarded numerous scholarships, was actively involved in campus politics, and was mentored by notable professors such as psychologist Lewis Terman and legal scholar Harry Rathbun. Eisner graduated with a BA in 1937. That same year, she married Stanford mechanical engineering student Willard Eisner and the two moved to Santa Monica, where Willard found employment with the RAND Corporation, a think tank founded immediately after WWII to provide research and analysis to U.S. military planning.

In the years following her graduation, Eisner took an interest in mysticism, meditation, and unconscious exploration. She studied spiritual and psychological practices at California retreat centres such as Jiddu Krishnamurti’s Arya Vihara, Gerald Heard’s Trabuco College, and the Sequoia Seminar, an annual summer gospel study retreat in the San Francisco Bay Area led by Harry Rathbun and his wife, Emilia. The Sequoia Seminar was an especially influential site for Eisner. Founded by the Rathbuns in 1946, the Seminar was focused on modernized readings of the bible as a text about the psychology of moral leadership and the fulfillment of personal potential. In addition to the gospels, Seminarians read psychological theories of creativity, individuation, and mystical experiences. The Sequoia Seminar thus exposed Eisner to a spiritual model of depth psychology that was explored in a group format.

Eisner attended the Sequoia Seminar annually. In 1951, she applied to study clinical psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), citing the influence of a Seminar session on Rorschach therapy. She was accepted to study under the supervision of Bruno Klopfer, founder of the Rorschach Institute and a major proponent of Jungian analytic psychology. For her dissertation, Eisner administered Rorschach tests to women who experienced infertility with no discernible organic cause, with the intention of finding unconscious origins for their infertility. To learn clinical practice, Eisner applied for an internship at a Veterans’ Administration (VA) psychiatric hospital. However, her application was nearly rejected on the basis that UCLA did not permit women to intern at VA hospitals, much less a married woman with one young child and the possibility of having more (Eisner and her husband had their first child, a daughter, in 1952). Eisner’s department had preferred she intern with UCLA’s child clinic or student health centre, depriving her of the chance to study applications of psychotherapy to psychosis and other acute psychiatric diagnoses. To rectify this, Eisner confronted her administration tirelessly, threatening to take her complaints of discrimination to the public if the policy was not changed. She succeeded in circumventing the ban and graduated with a PhD in clinical psychology in 1956.

While finishing her dissertation, Eisner came across a bulletin for a graduate research assistant position in an experimental drug study. She had a hunch that drug was LSD, a new hallucinogen from Switzerland that had just begun making inroads into American psychiatry in the early 1950s. She had just heard of the drug at a recent Sequoia Seminar workshop facilitated by British philosopher Gerald Heard, who spoke of its ability to produce mystical experiences. Too busy working on her dissertation to apply for the position, Eisner nonetheless contacted the study director Sidney Cohen to volunteer as a participant. In November of 1955, Eisner arrived at the Brentwood VA Hospital to take a 100ug dose of LSD and submit to an evaluation of her “ego functioning.” Cohen administered then-common assessment instruments such as the TAT and MMPI. Eisner found the tasks to be tedious distractions from the LSD experience, which otherwise pulled her toward deep psychological and spiritual insights. Though the experiment used LSD to explore the structure of the mind, participation in the study had given Eisner a feel for the drug’s therapeutic potential.

Eisner’s participation in the study had a remarkable impact on her life. Inspired to work with LSD as a clinician, Eisner maintained regular communication with Cohen until her graduation, after which Cohen hired her to co-investigate the therapeutic properties of LSD at the Brentwood VA Hospital. Between 1956 and 1959, Eisner and Cohen were primary collaborators, co-authoring numerous studies on LSD’s clinical applications. Their research received widespread attention primarily for two features. One was their use of low doses of LSD that were gradually increased over many sessions. Until that time, most LSD studies had used high doses of the drug to investigate states that resembled psychosis. Contrarily, Cohen and Eisner started patients on 25ug, because they noticed that low doses kept patients grounded enough to communicate clearly with the therapist, but affected enough to form novel associations, engage in more free-flowing honesty about their internal experience, and recall long-repressed trauma. The other unique dimension to their work was their codification of the “integrative experience.” Characteristics of an integrative experience included a sense of peace with one’s life conditions, a cathartic release of a trauma’s emotional burden, and a deep, spiritual feeling of one’s interconnectedness with the world. The reliability with which LSD produced integrative experiences led Eisner and Cohen to the conclusion that the drug dismantled ego defenses, which opened up space for catharsis and healing. By the early 1960s, Eisner and other practitioners who employed low doses of LSD in psychodynamic therapy consolidated the model under the term “psycholytic therapy.”

Eisner was a passionate proponent of psycholytic therapy. She was an active member of the psychedelic psychiatry community, presenting at conferences in the United States and Europe and forming close relationships with important figures in the field such as Humphrey Osmond and Ronald Sandison. In 1961, Eisner participated in the formation of the Association for Psycholytic Therapy (APT), an organization that counted her among the “founding fathers” of psycholytic therapy. Her inclusion as a founder was not without debate. Europe was home to most of the world’s psycholytic therapists, but the European practitioners were mainly psychiatrists who resisted the notion of a psychologist providing drug treatment. Despite its appearance as a professional disagreement, the marginalization of psychologists was also highly gendered, as many more women were psychologists than psychiatrists at the time. This was not lost on Eisner, who confided to a colleague her suspicion that the APT sought to exclude her based on her gender. Nonetheless, Eisner was able to argue her point that her experience practicing, researching, and representing psycholytic therapy at conferences warranted her inclusion as a founder of the field.

In her private practice, Eisner experimented with a multitude of methods for producing psycholytic states besides LSD. These methods included Ritalin, carbogen (a mixture of 70% oxygen and 30% carbon dioxide), and in later years, ketamine, bodywork, and hydrotherapy. These experiments came partly because of growing restrictions against the experimental and therapeutic use of LSD. Until the early 1960s, LSD was relatively easily available to health practitioners affiliated with hospitals or research programs. As the drug became increasingly available to the public and eventually took on an emblematic role in the 1960s counterculture, its manufacturer’s distribution policies became more stringent. By 1969, the United States outlawed all uses of LSD. Additionally, Eisner’s relationship with the psychedelic psychotherapy community was fracturing; it was more difficult to collaborate with her European colleagues than she had anticipated, and soon the APT petered out, only to reappear in 1964 as the psychiatry-focused European Medical Society of Psycholytic Therapy (EPT).

Eisner adapted to the limitations imposed on LSD work. Between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s, Eisner focused on developing her group therapy practice. Group therapy with Eisner involved many of the techniques associated with the humanistic, gestalt, and transpersonal therapies of the countercultural era. Clients participated in encounter groups, some of which lasted through the night. They often involved the administration of psycholytic substances; LSD in the beginning, and later Ritalin and Ketamine. Eisner facilitated the group through somatic activities and relational encounters designed to dismantle clients’ ego defences and put them in touch with their primary emotions and repressed memories. She also achieved this using nonverbal methods such as hot mineral baths and a form of massage called “Rolfing.” These methods often facilitated emotional releases and memory relivings that Eisner attributed not only to repressed personal memory, but also past-life memory. Eisner’s intention was to establish not just a group therapy practice, but a therapeutic community of clients who lived together and incorporated psychospiritual healing into every aspect of their social lives. At its height, Eisner’s community had more than forty members living in houses and apartments that Eisner’s family owned in the Santa Monica area.

Although Eisner’s practices and explanations contravened the evidentiary and client-therapist boundary conventions of clinical psychology, they were part of a trend toward spirituality and radical authenticity that came to be identified as transpersonal psychology. Nonetheless, Eisner’s proclivity for therapeutic practices that challenged convention and reached for spiritual and supernatural explanations eventually got her into deep trouble that culminated in the loss of her clinical license. In 1976, one of Eisner’s clients died under treatment that involved a mineral bath, Rolfing and Ritalin ingestion. Following this event, the California Board of Medical Quality Assurance (BMQA) conducted a wrongful death investigation against Eisner. They obtained affidavits from clients that revealed a host of concerning accusations: Eisner was purported to charge clients for mandatory sessions, deter them from seeking medical attention for injuries garnered during ketamine and Rolfing sessions, give them LSD under the guise of a different drug, and subject them to physically and emotionally harmful treatments against their wills. Additionally, the BMQA’s expert witnesses reprimanded Eisner for her use of treatments that had no basis in scientific evidence and her lack of adherence to drug safety protocols. In 1978, the BMQA revoked Eisner’s license to practice psychology.

Eisner tried to reinstate her license in the 1980s to no avail. Instead, she reestablished her connection to the psychedelic research community through organizational work. In 1988, the Albert Hofmann Foundation was launched in honour of Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who first synthesized LSD. The non-profit foundation was dedicated to preserving the history of psychedelic science. Eisner was a director and advisor of the foundation, sitting alongside former colleagues and important figures in psychedelic history such as Abram Hoffer, Myron Stolaroff, Oscar Janiger, Ram Dass, and Rick Doblin. Her tasks included planning conferences and events, including the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of LSD’s origins in 1994. In 2001, Eisner donated volumes of personal and professional documents to the Stanford University Library Archives. In 2002, she wrote a memoir of her professional life. Titled Remembrances of LSD Therapy Past, the memoir was not published, but is freely available online. Eisner passed away July 1st, 2004, in Santa Monica, California.

By Tal Davidson (2020)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Betty Eisner

Cohen, S., & Eisner, B. G. (1959). Use of lysergic acid diethylamide in a psychotherapeutic setting. AMA Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry, 81(5), 615-619.

Eisner, B. G. (1963). The influence of LSD on unconscious activity. In R. Crocket, R. Sandison & A. Walk, (Eds.), Hallucinogenic drugs and their psychotherapeutic use: The proceedings of the quarterly meeting of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association in London, February 1961 (141-145). London: HK Lewis & Co.

Eisner, B. G. (1964). Notes on the use of drugs to facilitate group psychotherapy. Psychiatric Quarterly, 38(1), 310-328.

Eisner, B. G. (1967). The importance of the non-verbal. In H.A. Abramson (Ed.), The use of LSD in psychotherapy and alcoholism (542 – 560). Indianapolis: The Bobb-Merrill Company.

Eisner, B. G. (1997). Bodywork and psychological healing. Journal of mind-body health, 13(3), 64-66.

Eisner, B. G. (2002). Remembrances of LSD therapy past. Retrieved from http://www.erowid.org/culture/characters/eisner_betty/remembrances_lsd_therapy. pdf.

Eisner, B. G. (2005). The birth and death of psychedelic therapy. In Walsh, R. Grob, C.S. (Eds.), Higher wisdom: Eminent elders explore the continuing impact of psychedelics (91-101). Albany: State University of New York.

About Betty Eisner

Gelber, S. M., & Cook, M. L. (1990). Saving the Earth: The history of a middle-class millenarian movement. Berkeley: University of California.

Novak, S. (1997). LSD before Leary: Sidney Cohen's Critique of 1950s Psychedelic Drug Research. Isis, 88(1), 87-110.

Davidson, T. (2017). The past lives of Betty Eisner: Examining the spiritual psyche of early psychedelic therapy through the story of an outsider, a pioneer, and a villain. [Master's thesis, York University]. YorkSpace Institutional Repository.