Profile

E. Kitch Childs

Birth:

1937

Death:

1993

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of Chicago (1972)

MSc, University of Chicago

BSc, University of Pittsburgh

Primary Affiliation(s):

Private Practice, Oakland, CA (1973-1990)

Other Media:

Career Focus:

Feminist therapy; anti-oppression; anti-racism and anti-sexism activism; healing Women of Colour communities; decriminalization of sex work.

Biography

E. Kitch Childs, born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, kept secret the meaning of her first initial and was thus called “Kitch” by friends and colleagues. Raised by her grandmother, she was the youngest child in a family of older brothers. She was a private woman and not much is documented about her childhood or family life. She did often speak with great pride about her oldest brother, Kenny Clarke (1914-1985), an acclaimed jazz drummer. Childs herself had a beautiful singing voice; in fact, during her time in graduate school, she was listed as “folk singer, E. Kitch Childs” on a program for an all-night environmental “Teach-Out” at Northwestern University in 1971.

Large protests like the Teach-Out were common occurrences in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. This was a time of national action for causes such as the Civil Rights Movement and ending the war in Vietnam. Despite the rallies and cries for equality and peace, Chicago was the site of extreme segregation and violence, where federal district judge Richard B. Austin warned in 1969: "Existing patterns of racial segregation must be reversed if there is to be a chance of averting the desperately intensifying division of whites and Negroes in Chicago." It was in this climate of civil resistance to ever-present oppression that Childs earned her Masters and PhD in Human Development at the University of Chicago, making her one of the first African-American women to do so. Her PhD allowed her to register as a clinical psychologist.

Despite this early success, Childs was not immune to the harsh consequences of profound racism. She lost two of her brothers to racial violence and believed strongly that Black Americans were dying from heart attacks and high blood pressure due to the stresses of racism. She knew that getting a higher education was a way to empower herself and gain enough social standing to effect change. While still a graduate student, capitalizing on the momentum of the Women’s Liberation movement, she helped found the Association for Women in Psychology (AWP) and the University of Chicago’s Gay Liberation Front, both in 1969. She also spoke out against anti-Semitism and enjoyed sprinkling her sassy tongue with Yiddish words. Childs was a part of the inner circles of many subversive movements, and thus interacted with colleagues and friends from diverse socio-cultural situations.

Immediately following her graduation, Childs moved to Oakland, California. There she opened a private practice in 1973. She continued her passion for advocacy, participating in some of the first meetings of the sex workers’ rights organization, COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), founded by Margot St. James and supported by such political celebrities as lawyer Florynce Kennedy, whom Kitch knew well. Sex workers and their allies demanded respect, freedom from police harassment, and the decriminalization of prostitution. In her private practice, Childs offered a sliding scale that dropped as low as $0/hr to help the most marginalized people, including those who were living with a new stigmatizing illness, AIDS.

She granted access to therapy for communities that were traditionally mistrustful of such services through a client-therapist model that attempted to eliminate barriers associated with hierarchies. For example, both client and therapist would assess suitability of the therapy, for this sharing of responsibility “tends to place [the client’s] presenting issues into a more appropriate focus as some of her life’s vicissitudes, and not as a major test of her ability to remain alive” (Childs, 1990, p. 198). When a client came in to see Childs, they were coming to her home; a big yellow house with a large “hang-out” porch. Therapy took place in her living room, both client and therapist sitting on the floor speaking to each other on level ground. She practiced feminist therapy, firmly guided by the client’s strengths and fostering of her self-esteem and feelings of competence. However, the modality she favoured was group therapy because it created a sense of community and thus allowed for group affirmation of the once-alienated individual client.

Childs began an article in Feminist Ethics in Psychotherapy (1990) with the fact that in 1984, only 10 clinical psychologists in America were listed as both Black and interested in women’s issues. For Black women, let alone the 28 million African-American citizens (Census Bureau, 1984), however, finding a psychologist who empathized with their unique perspectives and needs was a challenge for many reasons beyond these numbers: “The reality of Black women’s lives incorporates racism, classism, and the host of other negative attitudes held toward Persons of Color in America…Abuse, stereotyping, and vilification about skin coloration, sexuality, ugliness, and stupidity remain rampant in contemporary American life” (Childs, 1990, p. 196). However, there is a danger in treating a client in terms of a generalized understanding of her culture, for each woman is unique. “The risk of losing this awareness is greater if the client is ‘other,’ and/or if the therapist’s stereotypical thinking is entrenched and not monitored” (Childs, 1990, p. 197). With this caveat in mind, Childs published on the distinct experiences of Black women and a feminist approach to therapy that permits a client to “generate her own comprehension” (Childs, 1990, p. 198) of the implications of her history, to confront her emotions, and to develop her own goals.

Black women came to Childs with issues of trust, rage and grief. Clients expressed a general feeling of somehow being ontologically “wrong”, which manifested itself as abuse against the therapist or even as self-abuse; thus, the prevention of early termination from therapy became key. Framing the client’s emotions in terms of her unique experiences of intersecting forms of oppression enabled her to own her anger and understand it as “a natural response to the years of repression of her own feelings” (Childs, 1990, p. 199). With ownership often came transformation of anger into grief and more creative forms of self-expression.

By the late 1980s, Childs had lost many of her friends and acquaintances to AIDS and was ready for a change. After two sizable earthquakes hit California in 1989 and 1991, she called up her friend psychologist Gail Pheterson in Paris and said, “When you can’t count on the ground standing still, it’s time to leave.” Less than a month later, she was in Europe. She landed in Paris and explored the city, its culture, and hoping to perhaps locate Kenny Clarke’s family, including renowned jazz singer Carmen McRae, who lived there. During visits to Amsterdam, she found greater affinity and linguistic ease in Dutch than French feminist communities, and she decided to move to Amsterdam where she remained for the last two years of her life. She quickly became involved with several groups, such as “Flamboyant,” a national documentation center for Black and migrant women. In 1992, at a conference held by the International Association of Women Philosophers, she presented a paper on racism and the phenomenon of tokenism. Women of Color, she argued, were either excluded or existed in the smallest numbers in any European or American organization despite the fact that seventy-five percent of the world was “colored.” In one of her last talks before her premature death in 1993, she spoke again of a solution:

"Any approach which evades the production of guilt and denial can do more to expedite the erasure of racism than other approaches…We must generate a systematic method for conflict resolution so as to lose none of the power of our anger in useless wheel spinning. Being angry is not the end of the relation, nor of the conflict, we must agree to hear and listen to hard, difficult to hear, words and ideas. By so doing we may amplify and augment sisterly cooperation, understanding and in the meantime enhance our self empowerment." (Childs, 1992, p. 296)

by Prapti Giri (2014)

With the help of Dr. Gail Pheterson

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Childs, E. Kitch (1992). Racism in the International Women’s Movement. In Maja Pellikaan-Engel (Eds.), Against patriarchal thinking: Proceedings of the VIth Symposium of the International Association of Women Philosophers (IAPh) 1992. (pp. 293-296). Amsterdam: VU University Press.

Childs, E. Kitch (1990). Therapy, feminist ethics, and the Community of Color with particular emphasis on the treatment of Black women. In H. Lerman & N. Porter (Eds.), Feminist ethics in psychotherapy. (pp. 195-203). Springer.

Childs, E. Kitch (1972). Prediction of Outcome in Encounter Groups: Outcome as a Function of Selected Personality Correlates, dissertation, University of Chicago, Committee on Human Development, Chicago, IL.

Childs, E. Kitch (1966). Careers in the military service; a review of the literature. Military Man Power Survey: Working Paper. (no. 4) National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, IL.

About E. Kitch Childs

Richardson, W. (2017). Feminist therapy pioneer: E. Kitch Childs. Women & Therapy, 40(3-4), 301-307.

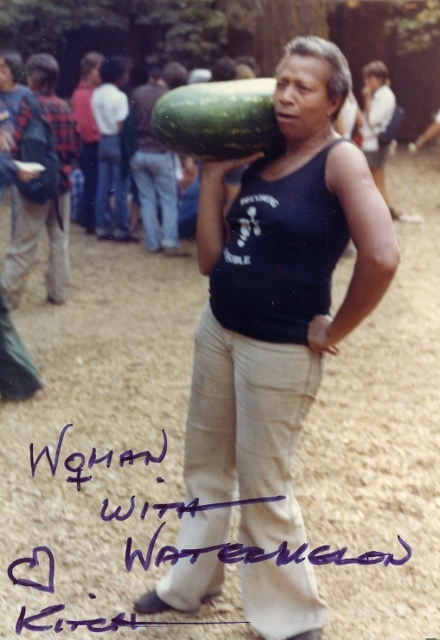

Photo Gallery

E. Kitch Childs

Birth:

1937

Death:

1993

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of Chicago (1972)

MSc, University of Chicago

BSc, University of Pittsburgh

Primary Affiliation(s):

Private Practice, Oakland, CA (1973-1990)

Other Media:

Career Focus:

Feminist therapy; anti-oppression; anti-racism and anti-sexism activism; healing Women of Colour communities; decriminalization of sex work.

Biography

E. Kitch Childs, born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, kept secret the meaning of her first initial and was thus called “Kitch” by friends and colleagues. Raised by her grandmother, she was the youngest child in a family of older brothers. She was a private woman and not much is documented about her childhood or family life. She did often speak with great pride about her oldest brother, Kenny Clarke (1914-1985), an acclaimed jazz drummer. Childs herself had a beautiful singing voice; in fact, during her time in graduate school, she was listed as “folk singer, E. Kitch Childs” on a program for an all-night environmental “Teach-Out” at Northwestern University in 1971.

Large protests like the Teach-Out were common occurrences in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. This was a time of national action for causes such as the Civil Rights Movement and ending the war in Vietnam. Despite the rallies and cries for equality and peace, Chicago was the site of extreme segregation and violence, where federal district judge Richard B. Austin warned in 1969: "Existing patterns of racial segregation must be reversed if there is to be a chance of averting the desperately intensifying division of whites and Negroes in Chicago." It was in this climate of civil resistance to ever-present oppression that Childs earned her Masters and PhD in Human Development at the University of Chicago, making her one of the first African-American women to do so. Her PhD allowed her to register as a clinical psychologist.

Despite this early success, Childs was not immune to the harsh consequences of profound racism. She lost two of her brothers to racial violence and believed strongly that Black Americans were dying from heart attacks and high blood pressure due to the stresses of racism. She knew that getting a higher education was a way to empower herself and gain enough social standing to effect change. While still a graduate student, capitalizing on the momentum of the Women’s Liberation movement, she helped found the Association for Women in Psychology (AWP) and the University of Chicago’s Gay Liberation Front, both in 1969. She also spoke out against anti-Semitism and enjoyed sprinkling her sassy tongue with Yiddish words. Childs was a part of the inner circles of many subversive movements, and thus interacted with colleagues and friends from diverse socio-cultural situations.

Immediately following her graduation, Childs moved to Oakland, California. There she opened a private practice in 1973. She continued her passion for advocacy, participating in some of the first meetings of the sex workers’ rights organization, COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), founded by Margot St. James and supported by such political celebrities as lawyer Florynce Kennedy, whom Kitch knew well. Sex workers and their allies demanded respect, freedom from police harassment, and the decriminalization of prostitution. In her private practice, Childs offered a sliding scale that dropped as low as $0/hr to help the most marginalized people, including those who were living with a new stigmatizing illness, AIDS.

She granted access to therapy for communities that were traditionally mistrustful of such services through a client-therapist model that attempted to eliminate barriers associated with hierarchies. For example, both client and therapist would assess suitability of the therapy, for this sharing of responsibility “tends to place [the client’s] presenting issues into a more appropriate focus as some of her life’s vicissitudes, and not as a major test of her ability to remain alive” (Childs, 1990, p. 198). When a client came in to see Childs, they were coming to her home; a big yellow house with a large “hang-out” porch. Therapy took place in her living room, both client and therapist sitting on the floor speaking to each other on level ground. She practiced feminist therapy, firmly guided by the client’s strengths and fostering of her self-esteem and feelings of competence. However, the modality she favoured was group therapy because it created a sense of community and thus allowed for group affirmation of the once-alienated individual client.

Childs began an article in Feminist Ethics in Psychotherapy (1990) with the fact that in 1984, only 10 clinical psychologists in America were listed as both Black and interested in women’s issues. For Black women, let alone the 28 million African-American citizens (Census Bureau, 1984), however, finding a psychologist who empathized with their unique perspectives and needs was a challenge for many reasons beyond these numbers: “The reality of Black women’s lives incorporates racism, classism, and the host of other negative attitudes held toward Persons of Color in America…Abuse, stereotyping, and vilification about skin coloration, sexuality, ugliness, and stupidity remain rampant in contemporary American life” (Childs, 1990, p. 196). However, there is a danger in treating a client in terms of a generalized understanding of her culture, for each woman is unique. “The risk of losing this awareness is greater if the client is ‘other,’ and/or if the therapist’s stereotypical thinking is entrenched and not monitored” (Childs, 1990, p. 197). With this caveat in mind, Childs published on the distinct experiences of Black women and a feminist approach to therapy that permits a client to “generate her own comprehension” (Childs, 1990, p. 198) of the implications of her history, to confront her emotions, and to develop her own goals.

Black women came to Childs with issues of trust, rage and grief. Clients expressed a general feeling of somehow being ontologically “wrong”, which manifested itself as abuse against the therapist or even as self-abuse; thus, the prevention of early termination from therapy became key. Framing the client’s emotions in terms of her unique experiences of intersecting forms of oppression enabled her to own her anger and understand it as “a natural response to the years of repression of her own feelings” (Childs, 1990, p. 199). With ownership often came transformation of anger into grief and more creative forms of self-expression.

By the late 1980s, Childs had lost many of her friends and acquaintances to AIDS and was ready for a change. After two sizable earthquakes hit California in 1989 and 1991, she called up her friend psychologist Gail Pheterson in Paris and said, “When you can’t count on the ground standing still, it’s time to leave.” Less than a month later, she was in Europe. She landed in Paris and explored the city, its culture, and hoping to perhaps locate Kenny Clarke’s family, including renowned jazz singer Carmen McRae, who lived there. During visits to Amsterdam, she found greater affinity and linguistic ease in Dutch than French feminist communities, and she decided to move to Amsterdam where she remained for the last two years of her life. She quickly became involved with several groups, such as “Flamboyant,” a national documentation center for Black and migrant women. In 1992, at a conference held by the International Association of Women Philosophers, she presented a paper on racism and the phenomenon of tokenism. Women of Color, she argued, were either excluded or existed in the smallest numbers in any European or American organization despite the fact that seventy-five percent of the world was “colored.” In one of her last talks before her premature death in 1993, she spoke again of a solution:

"Any approach which evades the production of guilt and denial can do more to expedite the erasure of racism than other approaches…We must generate a systematic method for conflict resolution so as to lose none of the power of our anger in useless wheel spinning. Being angry is not the end of the relation, nor of the conflict, we must agree to hear and listen to hard, difficult to hear, words and ideas. By so doing we may amplify and augment sisterly cooperation, understanding and in the meantime enhance our self empowerment." (Childs, 1992, p. 296)

by Prapti Giri (2014)

With the help of Dr. Gail Pheterson

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Childs, E. Kitch (1992). Racism in the International Women’s Movement. In Maja Pellikaan-Engel (Eds.), Against patriarchal thinking: Proceedings of the VIth Symposium of the International Association of Women Philosophers (IAPh) 1992. (pp. 293-296). Amsterdam: VU University Press.

Childs, E. Kitch (1990). Therapy, feminist ethics, and the Community of Color with particular emphasis on the treatment of Black women. In H. Lerman & N. Porter (Eds.), Feminist ethics in psychotherapy. (pp. 195-203). Springer.

Childs, E. Kitch (1972). Prediction of Outcome in Encounter Groups: Outcome as a Function of Selected Personality Correlates, dissertation, University of Chicago, Committee on Human Development, Chicago, IL.

Childs, E. Kitch (1966). Careers in the military service; a review of the literature. Military Man Power Survey: Working Paper. (no. 4) National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, IL.

About E. Kitch Childs

Richardson, W. (2017). Feminist therapy pioneer: E. Kitch Childs. Women & Therapy, 40(3-4), 301-307.