Profile

Isabelle V. Kendig

Birth:

1889

Death:

1974

Training Location(s):

PhD, Radcliffe College (1933)

MA, Radcliffe College (1930)

AB, Oberlin College (1912)

Primary Affiliation(s):

League for Preventative Work, Boston (1915-16)

National Women’s Party, Washington DC (1922-23)

Pine Manor Junior College (1930-1936)

St. Elizabeths Hospital (1935-50)

National Institute for Mental Health (1955-1964)

Career Focus:

Eugenics; prevention of war; women's rights; clinical psychology.

Biography

Isabelle Kendig was educated at St. Xavier’s Academy in Chicago, a Catholic school. After high school, she attended Cook County Normal School, a teachers college known for its progressive philosophy and connections to Chicago’s poor and immigrant populations. She then became an elementary school teacher in the Chicago public schools. After three years of teaching she became a student again, attending Oberlin College and graduating Phi Beta Kappa. At Oberlin she was inspired by sociologist Albert B. Wolfe, who taught Socialism and Social Problems. She came to agree with his emphasis on schoolwork as preparation for engagement with the social problems of the day, which included disease, slums, poverty, and women’s second-class status. She also learned from him to value collectivism over individualism.

After college, Kendig served as a eugenic field worker, trained by Charles Davenport at the Eugenics Record Office in Long Island. Field work in eugenics was a popular job for young people, particularly women, who wanted to improve society by investigating the connection between heredity and social problems. Skeptical of the assumptions of hard-line eugenicists, Kendig collected data that contradicted their basic beliefs. When she presented her research at a eugenics conference, Kendig was shunned by Davenport, who, in turn, falsified her findings to fit his beliefs. Remarkable for someone with no psychological training, she also criticized intelligence tests for measuring the social deprivation of rural children rather than intelligence. After two years, Kendig gave up her role as researcher and became the executive secretary of a state-wide social service agency in Massachusetts, advocating for a new institution for people with intellectual disabilities (then known as the "feebleminded").

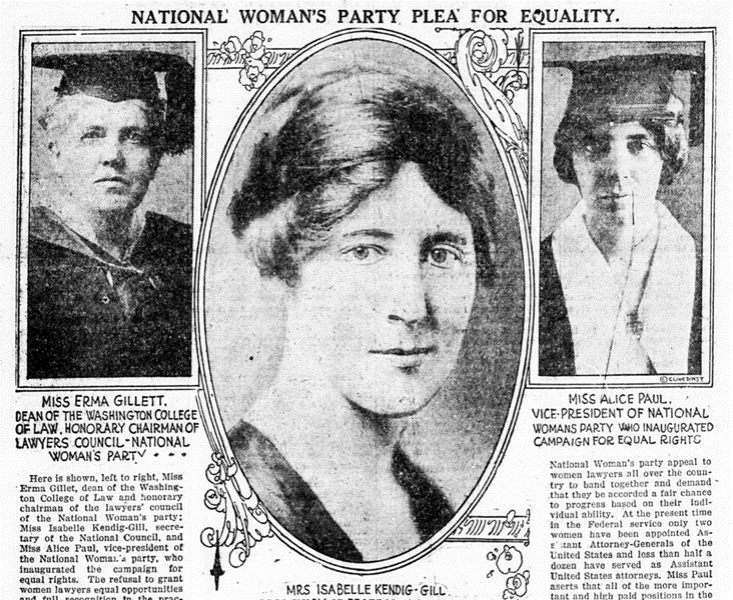

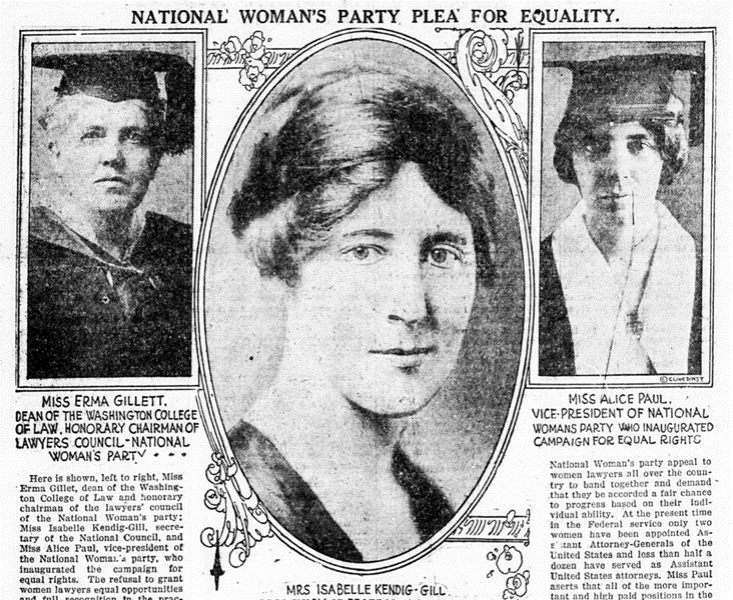

In her next career, Kendig was an activist in socialist, feminist, and anti-militarist organizations in Washington DC. In the National Women’s Party [NWP], she was a field organizer and its Legislative and Organizational Secretary. She lobbied and helped organize local groups in the South and created equal rights publicity material for a national audience. Kendig also created the NWP’s Councils for various professions and its Homemakers’ Council—a forum in which policies on marriage and family could be created. Speaking to the press, she offered advice on how women could maintain some financial independence in their marriage. This was a goal she pursued personally, with the collaboration of her husband, criminologist Howard Gill.

After leaving the Women's Party, Kendig gained national recognition as a founder and Executive Secretary of the Women’s Committee for Political Action. This national organization of socialists, feminists, and anti-militarists was founded to make sure women’s interests were represented in preparations for the election of 1924. A goal of the WCPA was to create a strong female presence within a larger group: the Conference on Progressive Political Action (CPPA), which launched the Presidential campaign for Robert (“Fighting Bob”) La Follette.

Kendig also worked for the anti-militarist National Council for the Prevention of War as a researcher and author. Among her projects was a survey and critique of the portrayal of war in history textbooks, which activists could use to argue for less militaristic schools. Kendig also served as the Washington representative of the American Civil Liberties Union. In that role she organized a campaign to oppose a bill for the registration and deportation of aliens, testifying before the relevant Congressional committee.

Kendig’s final career was in clinical psychology. She began by earning an M.A. and Ph.D. at Radcliffe College. As a graduate student she studied and conducted research at the Harvard Psychological Clinic under its director Henry Murray, who became a lifelong friend. There, she was a prominent member of a group of researchers that included future leaders of the field of clinical and personality psychology, including Saul Rosenzweig, Robert W. White, and Erik Erikson.

Following graduate school, she worked at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC, where she rose to the position of Chief Psychologist. One of her more newsworthy roles there was giving projective tests to the hospital's most famous patient, the poet Ezra Pound. She also taught at George Washington University Medical School and Catholic University and was President of the Washington DC Psychological Society. In the 1940s, Kendig published widely on assessment and psychopathology and completed a book on intellectual deterioration in schizophrenia that had been started by William Alanson White, former superintendent at St. Elizabeths. After WWII she helped lead the field of clinical psychology, locally and nationally, as it expanded its scientific and social influence. She ended her career as a researcher at the National Institute for Mental Health

To historians of psychology, Kendig qualifies as a noteworthy member of the second generation of women psychologists. One could argue, however, that her significance lies beyond psychology. In each of her three careers (eugenics, politics, and psychology) Isabelle Kendig was a prominent figure who showed independence of thought, innovative tactics, and desire to get credit for her own work. While other women suffered for their feminist views, Kendig managed to survive and prosper—pushing the boundaries of career possibilities for women.

by Ben Harris (2023)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Isabelle V. Kendig

Kendig, I. (1913). One Massachusetts family. Unpublished manuscript. American Eugenics Society Records, American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia, PA.

Kendig, I. (1924). War and peace in United States history textbooks. Washington, D.C.: National Council for Prevention of War.

Kendig, I. (1924). Women in the progressive movement. The Nation,

Nov. 29, p. 544.

Kendig, I. (1954). The basic Rorschach triad; A graphic schema of presentation. Journal of Projective Techniques, 18, 448–452.

Kendig, I. (1956). An adolescent topsy. Contemporary Psychology, 1, 246.

Kendig, I. (1963). The denial of illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 36, 37-47.

Kendig, I., & Richmond, W. V. (1940). Psychological studies in dementia praecox. Ann Arbor: Edwards.

About Isabelle V. Kendig

Bix, A. S. (1997). Experiences and voices of eugenics field-workers: “Women’s work” in biology. Social Studies of Science, 27, 625-668.

Dr. Isabelle Kendig, 84, Dies, Psychologist, Active in ACLU. Washington Post, September 25, 1974, p. C 10.

Gillman, R. D. (1994). Ezra Pound’s Rorschach diagnosis. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 58, 307-322.

Goodman, E. (1970, July 19). Women with a goal: End name-dropping. Boston Globe, p. A-8.

Harris, B. (2021). Eugenics, social reform, and psychology: The careers of Isabelle Kendig. History of Psychology, 24, 350-376.

Josefek, K. A. (1970, August 26). Suffragette says women have long way to go. New Bedford Standard-Times.

Photo Gallery

Isabelle V. Kendig

Birth:

1889

Death:

1974

Training Location(s):

PhD, Radcliffe College (1933)

MA, Radcliffe College (1930)

AB, Oberlin College (1912)

Primary Affiliation(s):

League for Preventative Work, Boston (1915-16)

National Women’s Party, Washington DC (1922-23)

Pine Manor Junior College (1930-1936)

St. Elizabeths Hospital (1935-50)

National Institute for Mental Health (1955-1964)

Career Focus:

Eugenics; prevention of war; women's rights; clinical psychology.

Biography

Isabelle Kendig was educated at St. Xavier’s Academy in Chicago, a Catholic school. After high school, she attended Cook County Normal School, a teachers college known for its progressive philosophy and connections to Chicago’s poor and immigrant populations. She then became an elementary school teacher in the Chicago public schools. After three years of teaching she became a student again, attending Oberlin College and graduating Phi Beta Kappa. At Oberlin she was inspired by sociologist Albert B. Wolfe, who taught Socialism and Social Problems. She came to agree with his emphasis on schoolwork as preparation for engagement with the social problems of the day, which included disease, slums, poverty, and women’s second-class status. She also learned from him to value collectivism over individualism.

After college, Kendig served as a eugenic field worker, trained by Charles Davenport at the Eugenics Record Office in Long Island. Field work in eugenics was a popular job for young people, particularly women, who wanted to improve society by investigating the connection between heredity and social problems. Skeptical of the assumptions of hard-line eugenicists, Kendig collected data that contradicted their basic beliefs. When she presented her research at a eugenics conference, Kendig was shunned by Davenport, who, in turn, falsified her findings to fit his beliefs. Remarkable for someone with no psychological training, she also criticized intelligence tests for measuring the social deprivation of rural children rather than intelligence. After two years, Kendig gave up her role as researcher and became the executive secretary of a state-wide social service agency in Massachusetts, advocating for a new institution for people with intellectual disabilities (then known as the "feebleminded").

In her next career, Kendig was an activist in socialist, feminist, and anti-militarist organizations in Washington DC. In the National Women’s Party [NWP], she was a field organizer and its Legislative and Organizational Secretary. She lobbied and helped organize local groups in the South and created equal rights publicity material for a national audience. Kendig also created the NWP’s Councils for various professions and its Homemakers’ Council—a forum in which policies on marriage and family could be created. Speaking to the press, she offered advice on how women could maintain some financial independence in their marriage. This was a goal she pursued personally, with the collaboration of her husband, criminologist Howard Gill.

After leaving the Women's Party, Kendig gained national recognition as a founder and Executive Secretary of the Women’s Committee for Political Action. This national organization of socialists, feminists, and anti-militarists was founded to make sure women’s interests were represented in preparations for the election of 1924. A goal of the WCPA was to create a strong female presence within a larger group: the Conference on Progressive Political Action (CPPA), which launched the Presidential campaign for Robert (“Fighting Bob”) La Follette.

Kendig also worked for the anti-militarist National Council for the Prevention of War as a researcher and author. Among her projects was a survey and critique of the portrayal of war in history textbooks, which activists could use to argue for less militaristic schools. Kendig also served as the Washington representative of the American Civil Liberties Union. In that role she organized a campaign to oppose a bill for the registration and deportation of aliens, testifying before the relevant Congressional committee.

Kendig’s final career was in clinical psychology. She began by earning an M.A. and Ph.D. at Radcliffe College. As a graduate student she studied and conducted research at the Harvard Psychological Clinic under its director Henry Murray, who became a lifelong friend. There, she was a prominent member of a group of researchers that included future leaders of the field of clinical and personality psychology, including Saul Rosenzweig, Robert W. White, and Erik Erikson.

Following graduate school, she worked at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC, where she rose to the position of Chief Psychologist. One of her more newsworthy roles there was giving projective tests to the hospital's most famous patient, the poet Ezra Pound. She also taught at George Washington University Medical School and Catholic University and was President of the Washington DC Psychological Society. In the 1940s, Kendig published widely on assessment and psychopathology and completed a book on intellectual deterioration in schizophrenia that had been started by William Alanson White, former superintendent at St. Elizabeths. After WWII she helped lead the field of clinical psychology, locally and nationally, as it expanded its scientific and social influence. She ended her career as a researcher at the National Institute for Mental Health

To historians of psychology, Kendig qualifies as a noteworthy member of the second generation of women psychologists. One could argue, however, that her significance lies beyond psychology. In each of her three careers (eugenics, politics, and psychology) Isabelle Kendig was a prominent figure who showed independence of thought, innovative tactics, and desire to get credit for her own work. While other women suffered for their feminist views, Kendig managed to survive and prosper—pushing the boundaries of career possibilities for women.

by Ben Harris (2023)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Isabelle V. Kendig

Kendig, I. (1913). One Massachusetts family. Unpublished manuscript. American Eugenics Society Records, American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia, PA.

Kendig, I. (1924). War and peace in United States history textbooks. Washington, D.C.: National Council for Prevention of War.

Kendig, I. (1924). Women in the progressive movement. The Nation, Nov. 29, p. 544.

Kendig, I. (1954). The basic Rorschach triad; A graphic schema of presentation. Journal of Projective Techniques, 18, 448–452.

Kendig, I. (1956). An adolescent topsy. Contemporary Psychology, 1, 246.

Kendig, I. (1963). The denial of illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 36, 37-47.

Kendig, I., & Richmond, W. V. (1940). Psychological studies in dementia praecox. Ann Arbor: Edwards.

About Isabelle V. Kendig

Bix, A. S. (1997). Experiences and voices of eugenics field-workers: “Women’s work” in biology. Social Studies of Science, 27, 625-668.

Dr. Isabelle Kendig, 84, Dies, Psychologist, Active in ACLU. Washington Post, September 25, 1974, p. C 10.

Gillman, R. D. (1994). Ezra Pound’s Rorschach diagnosis. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 58, 307-322.

Goodman, E. (1970, July 19). Women with a goal: End name-dropping. Boston Globe, p. A-8.

Harris, B. (2021). Eugenics, social reform, and psychology: The careers of Isabelle Kendig. History of Psychology, 24, 350-376.

Josefek, K. A. (1970, August 26). Suffragette says women have long way to go. New Bedford Standard-Times.