Profile

Leonore Tiefer

Birth:

1944

Training Location(s):

PhD, New York University (1988)

PhD, University of California (1969)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Private psychotherapy and sex therapy practice, Manhattan, NY

New York University School of Medicine

Colorado State University (1969-1977)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Other Media:

Interviews

The Misinformation Behind Female Viagra

Professional Websites

Archival Collections

Leonore Tiefer Collection, Kinsey Institute Library, Indiana University

New View Campaign Capstone Video

Panels

Women, Psychology and the Women’s Liberation Movement: Transforming Psychology

[panel presented as part of "A Revolutionary Moment" at Boston University, March, 2014]

Career Focus:

Sex research and therapy; medicalization of sexuality; feminist critique.

Biography

Once Leonore Tiefer "got" feminism, everything changed. In 1969, prior to developing her feminist consciousness, Tiefer received a PhD in experimental psychology and secured her first academic position at Colorado State University (CSU). She remembers being the only woman in a department of 27 people. She specialized in animal sexual behavior and worked in labs doing basic animal research. At the time she "didn't know anything about feminism." She recalls, "I was just hired to teach experimental and physiological psychology. I set up...an animal lab for research and three years passed." At that time, another woman entered the department who would transform Tiefer's thinking and ultimately her career.

As a junior academic, Tiefer was busy. She found herself spending 20 hours a day preparing lectures and examinations. She added to this the stresses of buying her first house and commuting to see her partner in Missouri. She had heard about women's marches, but told herself, "it has nothing to do with me." However, in the fall of 1972, the new female faculty member at CSU, an out-feminist-lesbian clinician, gave Tiefer some reading material that hit home. She realized that feminism had everything to do with her. After this awakening, Tiefer began building friendships with other women and spent her free time involved with feminist organizations. She began thinking, reading, and writing as a feminist. And nothing about animal research made sense anymore.

Before being exposed to this feminist literature, Tiefer had experienced sexism, but she didn't have the language for it. It was "just the way things were." She remembers being a graduate student of a prominent male researcher who would not hire her to work in his lab because of her gender. She also recalls that although he assisted her in looking for academic positions, "he didn't do much because he didn't believe that women stuck it out. He thought they quit, got married, and had babies." Eventually, he recommended Tiefer for a position at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. She recalls,

I was a Phi Beta Kappa student. I was crème de la crème in the brains department. So, he did write a letter to the chairman...and said, "I've got this student graduating that could really be good for your program," and we got a letter back, which I still have, saying, "the student sounds great, but we don't hire women."

Armed with her new-found knowledge of feminist theory, Tiefer felt bored watching rats in boxes. She began asking herself, "what does animal research tell us about human sexuality?" Tiefer feels that she actually has the "mind of a social psychologist," and is not sure why she did not pursue training in that field. Indeed, she feels that much of her training in psychology has been "accidental." She began her undergraduate degree as a history major, but quickly switched to psychology when someone urged her to pick a discipline that would make her employable. She feels like her graduate training was influenced by her former husband, who was a graduate student in philosophy. While she enjoyed philosophical thinking, she was frustrated by its lack of answers. Psychology offered a way of answering questions.

In the mid-1970s when Tiefer realized that she did not want to continue animal research, she took a sabbatical to study human sexuality. She also decided to get out of academia. After leaving Colorado, she worked at a New York hospital as a sex therapist. In hindsight she feels this career move wasn't entirely right. She recalls:

I had never taken a course in abnormal in my life, but I administered it and I did some sort of stupid research with patients and I began teaching medical students. I liked the colleagues and I liked the energy, but I felt more and more fraudulent.

This feeling of dishonesty impelled Tiefer to return to school to train as a clinical psychologist. She worked in the field of health until 1996 when she began a private practice. Part of the motivation to start her own practice was the narrow view the medical professions have of sex. She states, "they felt that the most important thing about sex was the mechanical operation of the genitalia." Tiefer continuously strives to infuse feminist principles and politics into sex therapy and theory, which of course includes more than the mechanics. It includes the social and cultural fabric of people's lives.

Tiefer feels that with the rise of medication like Viagra over the 1980s and 1990s, sex therapy began to die out. Urologists were able to assert themselves as the medical experts and no longer had much need for psychologists. Tiefer's involvement with medical institutions led to her important activism on female sexuality.

In 1998, when Viagra was approved by the Federal Drug Administration, people began asking about a similar drug for women. Tiefer felt this was a dangerous development. She began to devote her energy to analyzing the idea of a "Viagra for women" and lobbying against the drug Intrinsa and the medicalization of women's sexuality. She argues that a new disease is being created for women, one that promotes a very narrow image of women's sexual potential:

[Intrinsa] is being promoted as if it were a good thing, a choice and an expansion, but in the context of other things that women don't have, like comprehensive sex education, not to mention abortion rights, availability and coverage for safe contraception, then...in some ways, [Intrinsa] is much more to benefit men than women.

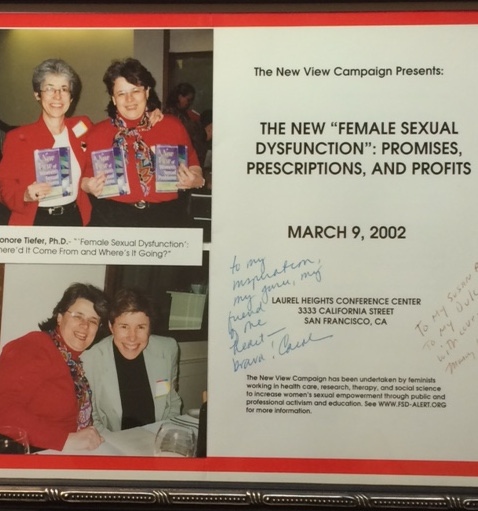

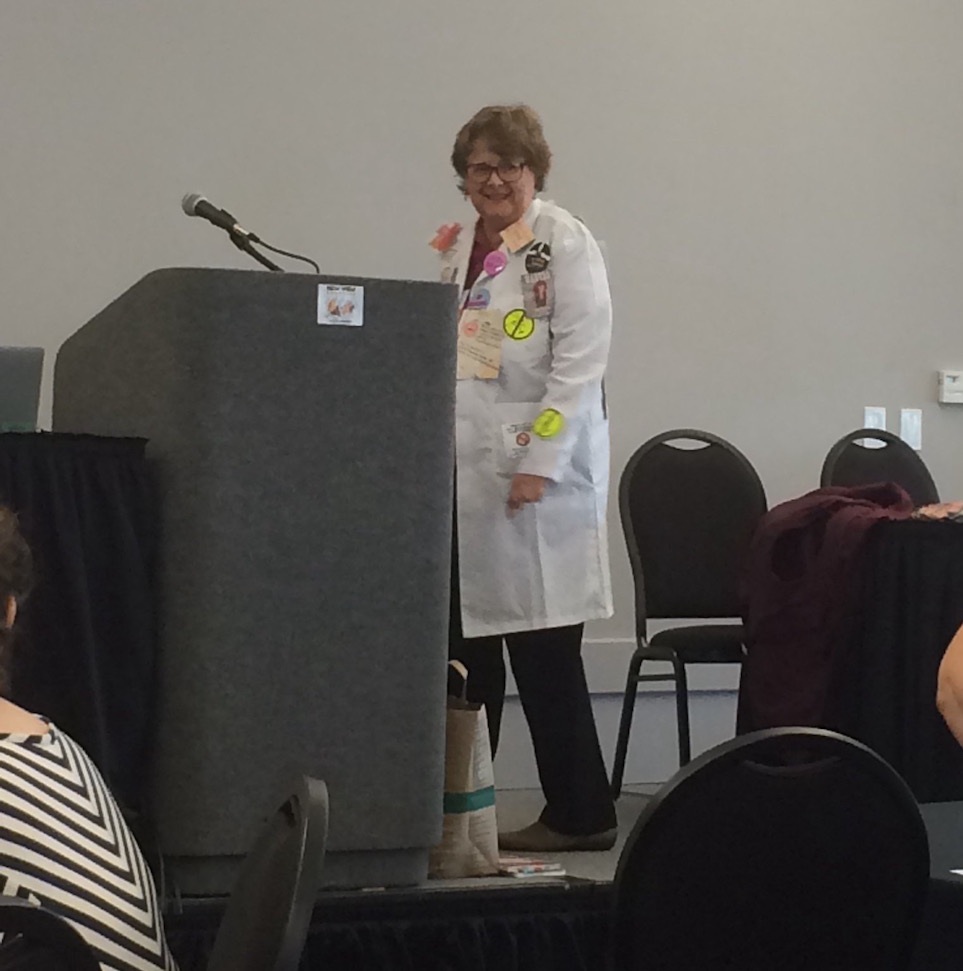

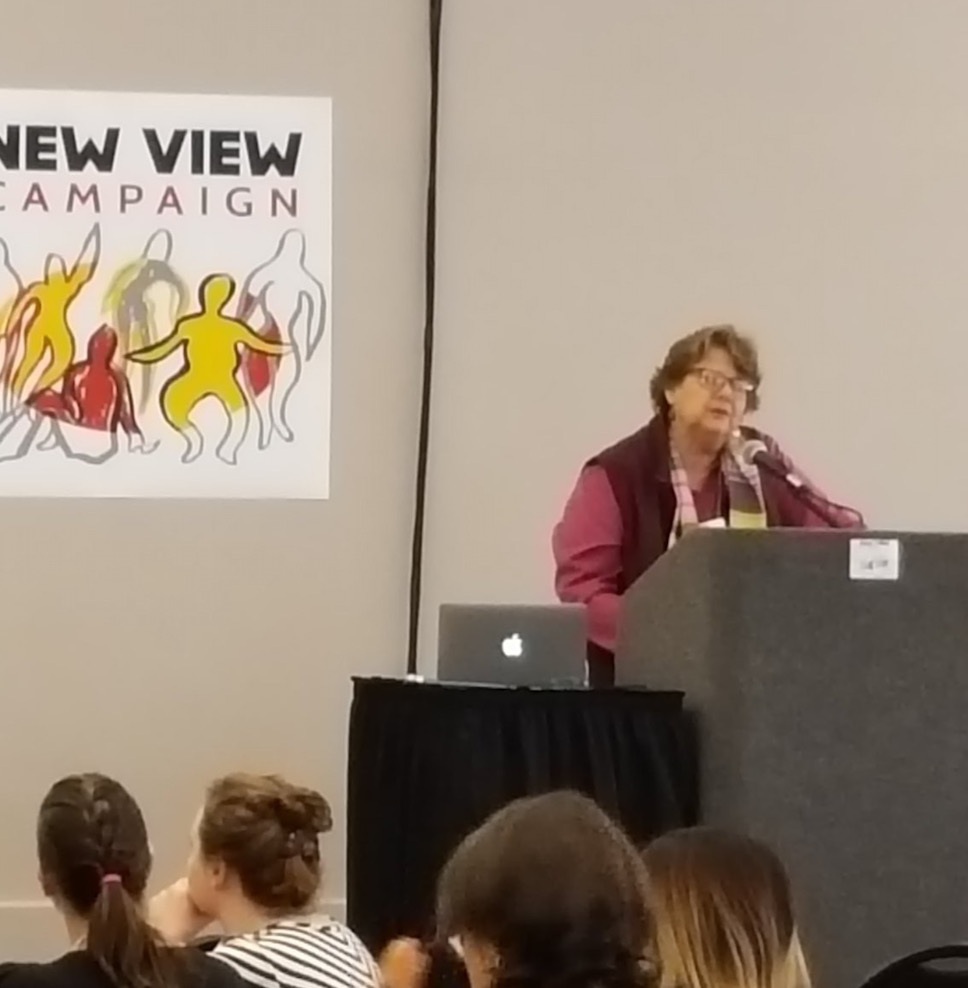

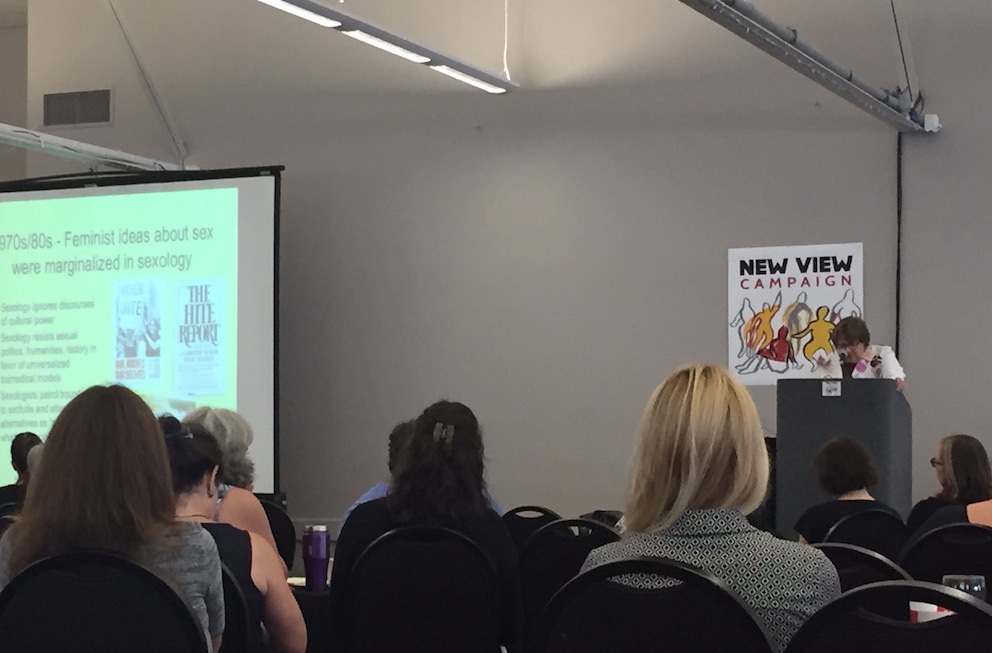

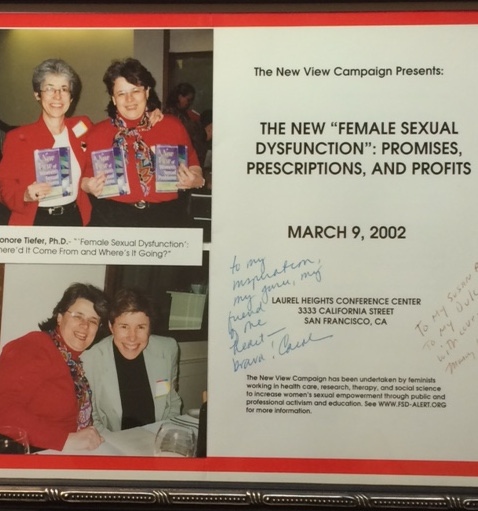

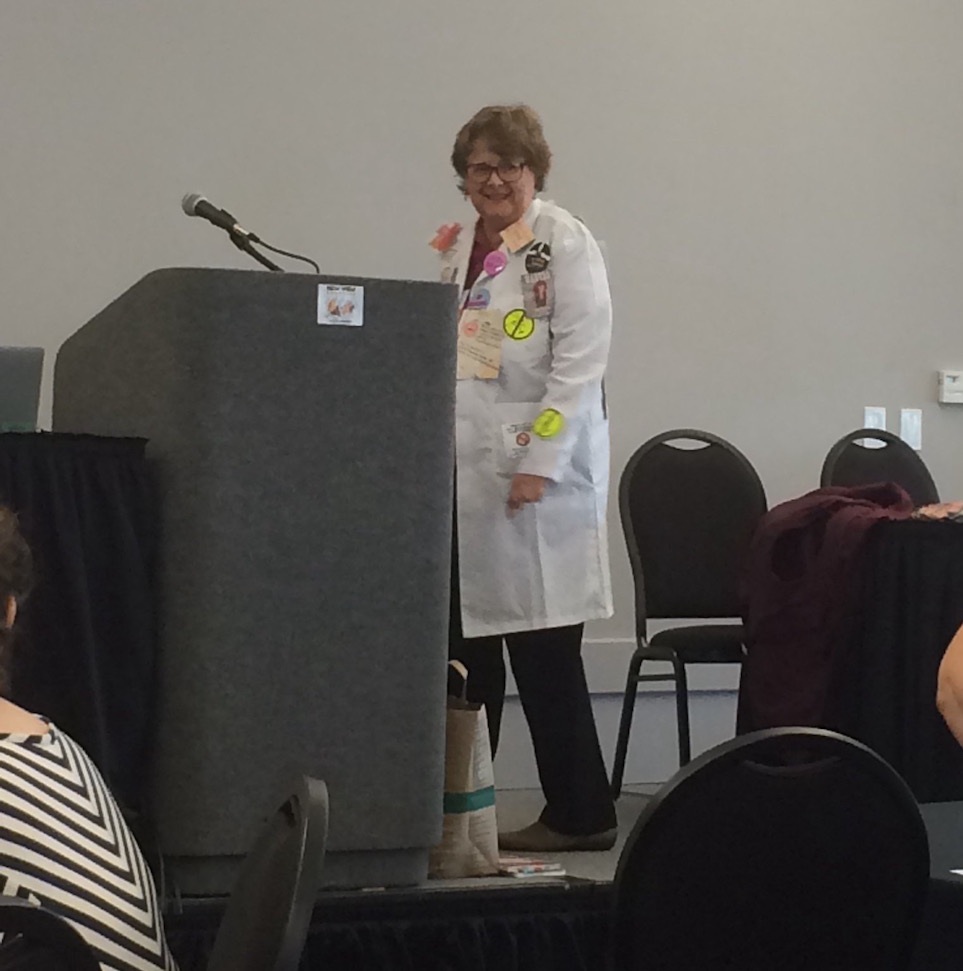

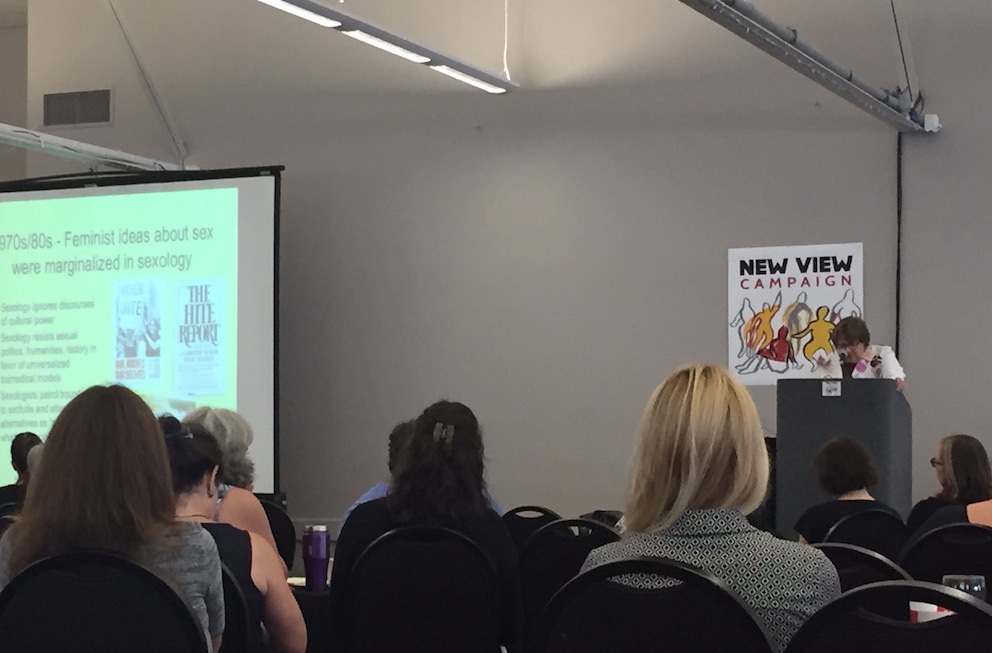

Her passion on this topic led to the establishment of the New View campaign in 2000. The New View seeks to confront, challenge, and disrupt the medicalization of female sexuality. Members of the New View have also engaged in efforts to challenge the growth of the female genital cosmetic surgery industry through their Vulvanomics campaign.

In 2014, female Viagra, now called flibanserin, again came up for FDA approval. Again, Tiefer and many others argued against the drug, but in August of 2015 it was approved after an intense lobbying campaign by Sprout, the pharmaceutical company producing it. Almost immediately after approval, Sprout was bought by the Canadian company Valeant for 1 billion dollars. Concerns about the (in)efficacy of the drug, how its use will be regulated, and its implications for how we view female sexuality, continue.

Tiefer does not feel that she became a political activist until 2000, but much of her energy has been and is devoted to political activism. Tiefer officially ended the New View Campaign in 2016 with a capstone conference at the Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana. She continues to believe, however, that social responsibility is of utmost importance and advises young feminist psychologists to be politically engaged. She warns that academia has the ability to suck your energy dry and that it is important to hold on to your energy and passion wherever you can. As she has noted in her article "An Activist in Sexology": "Since challenging the status quo is likely to make you unpopular, make sure you have a political base of some sort to provide moral support when the going gets rough."

by Jenna MacKay (2010) updated (2017)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

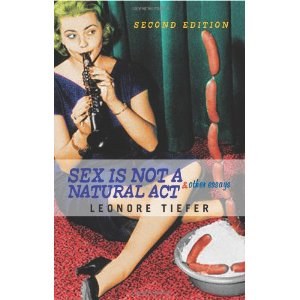

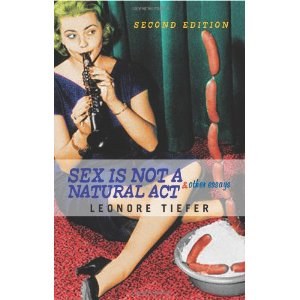

Tiefer, L. (2004). Sex is not a natural act and other essays, 2nd Edition. Boulder: Westview Press.

Kaschak, E., & Tiefer, L. (Eds.) (2001). A new view of women's sexual problems. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Tiefer, L. (2006). Female sexual dysfunction: A case study of disease mongering and activist resistance. PLoS Med 3(4): e178.

Tiefer, L. (2001). A new view of women's sexual problems: Why new? Why now?. The Journal of Sex Research, 38, 89-96.

Tiefer, L. (1996). The medicalization of sexuality: Conceptual, normative, and professional issues. Annual Review of Sex Research, 7, 252-282.

Tiefer, L. (1988). A feminist critique of the sexual dysfunction nomenclature. Women & Therapy, 7, 5-21.

Tiefer, L. (1986). In pursuit of the perfect penis: The medicalization of male sexuality. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 579-599.

Tiefer, L. (1978). The context and consequences of contemporary sex research: A feminist perspective. In W. McGill, D. Dewsbury, and B. Sachs (Eds.), Sex and behavior: Status and prospectus. New York: Plenum Press.

Photo Gallery

Leonore Tiefer

Birth:

1944

Training Location(s):

PhD, New York University (1988)

PhD, University of California (1969)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Private psychotherapy and sex therapy practice, Manhattan, NY

New York University School of Medicine

Colorado State University (1969-1977)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Other Media:

Interviews

The Misinformation Behind Female Viagra

Professional Websites

Archival Collections

Leonore Tiefer Collection, Kinsey Institute Library, Indiana University

New View Campaign Capstone Video

Panels

Women, Psychology and the Women’s Liberation Movement: Transforming Psychology

[panel presented as part of "A Revolutionary Moment" at Boston University, March, 2014]

Career Focus:

Sex research and therapy; medicalization of sexuality; feminist critique.

Biography

Once Leonore Tiefer "got" feminism, everything changed. In 1969, prior to developing her feminist consciousness, Tiefer received a PhD in experimental psychology and secured her first academic position at Colorado State University (CSU). She remembers being the only woman in a department of 27 people. She specialized in animal sexual behavior and worked in labs doing basic animal research. At the time she "didn't know anything about feminism." She recalls, "I was just hired to teach experimental and physiological psychology. I set up...an animal lab for research and three years passed." At that time, another woman entered the department who would transform Tiefer's thinking and ultimately her career.

As a junior academic, Tiefer was busy. She found herself spending 20 hours a day preparing lectures and examinations. She added to this the stresses of buying her first house and commuting to see her partner in Missouri. She had heard about women's marches, but told herself, "it has nothing to do with me." However, in the fall of 1972, the new female faculty member at CSU, an out-feminist-lesbian clinician, gave Tiefer some reading material that hit home. She realized that feminism had everything to do with her. After this awakening, Tiefer began building friendships with other women and spent her free time involved with feminist organizations. She began thinking, reading, and writing as a feminist. And nothing about animal research made sense anymore.

Before being exposed to this feminist literature, Tiefer had experienced sexism, but she didn't have the language for it. It was "just the way things were." She remembers being a graduate student of a prominent male researcher who would not hire her to work in his lab because of her gender. She also recalls that although he assisted her in looking for academic positions, "he didn't do much because he didn't believe that women stuck it out. He thought they quit, got married, and had babies." Eventually, he recommended Tiefer for a position at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. She recalls,

I was a Phi Beta Kappa student. I was crème de la crème in the brains department. So, he did write a letter to the chairman...and said, "I've got this student graduating that could really be good for your program," and we got a letter back, which I still have, saying, "the student sounds great, but we don't hire women."

Armed with her new-found knowledge of feminist theory, Tiefer felt bored watching rats in boxes. She began asking herself, "what does animal research tell us about human sexuality?" Tiefer feels that she actually has the "mind of a social psychologist," and is not sure why she did not pursue training in that field. Indeed, she feels that much of her training in psychology has been "accidental." She began her undergraduate degree as a history major, but quickly switched to psychology when someone urged her to pick a discipline that would make her employable. She feels like her graduate training was influenced by her former husband, who was a graduate student in philosophy. While she enjoyed philosophical thinking, she was frustrated by its lack of answers. Psychology offered a way of answering questions.

In the mid-1970s when Tiefer realized that she did not want to continue animal research, she took a sabbatical to study human sexuality. She also decided to get out of academia. After leaving Colorado, she worked at a New York hospital as a sex therapist. In hindsight she feels this career move wasn't entirely right. She recalls:

I had never taken a course in abnormal in my life, but I administered it and I did some sort of stupid research with patients and I began teaching medical students. I liked the colleagues and I liked the energy, but I felt more and more fraudulent.

This feeling of dishonesty impelled Tiefer to return to school to train as a clinical psychologist. She worked in the field of health until 1996 when she began a private practice. Part of the motivation to start her own practice was the narrow view the medical professions have of sex. She states, "they felt that the most important thing about sex was the mechanical operation of the genitalia." Tiefer continuously strives to infuse feminist principles and politics into sex therapy and theory, which of course includes more than the mechanics. It includes the social and cultural fabric of people's lives.

Tiefer feels that with the rise of medication like Viagra over the 1980s and 1990s, sex therapy began to die out. Urologists were able to assert themselves as the medical experts and no longer had much need for psychologists. Tiefer's involvement with medical institutions led to her important activism on female sexuality.

In 1998, when Viagra was approved by the Federal Drug Administration, people began asking about a similar drug for women. Tiefer felt this was a dangerous development. She began to devote her energy to analyzing the idea of a "Viagra for women" and lobbying against the drug Intrinsa and the medicalization of women's sexuality. She argues that a new disease is being created for women, one that promotes a very narrow image of women's sexual potential:

[Intrinsa] is being promoted as if it were a good thing, a choice and an expansion, but in the context of other things that women don't have, like comprehensive sex education, not to mention abortion rights, availability and coverage for safe contraception, then...in some ways, [Intrinsa] is much more to benefit men than women.

Her passion on this topic led to the establishment of the New View campaign in 2000. The New View seeks to confront, challenge, and disrupt the medicalization of female sexuality. Members of the New View have also engaged in efforts to challenge the growth of the female genital cosmetic surgery industry through their Vulvanomics campaign.

In 2014, female Viagra, now called flibanserin, again came up for FDA approval. Again, Tiefer and many others argued against the drug, but in August of 2015 it was approved after an intense lobbying campaign by Sprout, the pharmaceutical company producing it. Almost immediately after approval, Sprout was bought by the Canadian company Valeant for 1 billion dollars. Concerns about the (in)efficacy of the drug, how its use will be regulated, and its implications for how we view female sexuality, continue.

Tiefer does not feel that she became a political activist until 2000, but much of her energy has been and is devoted to political activism. Tiefer officially ended the New View Campaign in 2016 with a capstone conference at the Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana. She continues to believe, however, that social responsibility is of utmost importance and advises young feminist psychologists to be politically engaged. She warns that academia has the ability to suck your energy dry and that it is important to hold on to your energy and passion wherever you can. As she has noted in her article "An Activist in Sexology": "Since challenging the status quo is likely to make you unpopular, make sure you have a political base of some sort to provide moral support when the going gets rough."

by Jenna MacKay (2010) updated (2017)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Tiefer, L. (2004). Sex is not a natural act and other essays, 2nd Edition. Boulder: Westview Press.

Kaschak, E., & Tiefer, L. (Eds.) (2001). A new view of women's sexual problems. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Tiefer, L. (2006). Female sexual dysfunction: A case study of disease mongering and activist resistance. PLoS Med 3(4): e178.

Tiefer, L. (2001). A new view of women's sexual problems: Why new? Why now?. The Journal of Sex Research, 38, 89-96.

Tiefer, L. (1996). The medicalization of sexuality: Conceptual, normative, and professional issues. Annual Review of Sex Research, 7, 252-282.

Tiefer, L. (1988). A feminist critique of the sexual dysfunction nomenclature. Women & Therapy, 7, 5-21.

Tiefer, L. (1986). In pursuit of the perfect penis: The medicalization of male sexuality. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 579-599.

Tiefer, L. (1978). The context and consequences of contemporary sex research: A feminist perspective. In W. McGill, D. Dewsbury, and B. Sachs (Eds.), Sex and behavior: Status and prospectus. New York: Plenum Press.