Profile

Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Birth:

1914

Death:

2019

Training Location(s):

PhD, Swarthmore College (Honorary) (2003)

PhD, Yale University (Honorary) (1998)

Cert., Columbia Psychoanalytic Center (1948)

MA, Columbia University (1943)

BA, Cornell University (1938)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Meharry Medical College (1943-1946)

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (1963-1984)

Other Media:

Media Links

Changing the Face of Medicine Profile

The Fellowship of Reconciliation Profile

Awards and Recognitions

Swarthmore College Honorary Degree Citation

Obituaries and Tributes

Wall Street Journal tribute by daughter Sara Lawrence Lightfoot

Career Focus:

Psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, clinical psychology, psychiatry, children’s mental health

Biography

On August 19, 1914, Margaret Cornelia Morgan Lawrence was born in Harlem, New York to an Episcopal priest father and an elementary school teacher mother. Although her parents lived in Richmond, Virginia, they temporarily relocated to Harlem for her birth; their first son had died in 1912 from cogenital conditions in the local segregated hospital, and they believed the healthcare received up north would be better than in the Jim Crow south. Despite the virulence of racial discrimination, Lawrence shined from a young age, and had large ambitions to become a pediatric doctor to save children like her brother.

Lawrence grew up in the heavily segregated Vicksburg, Mississippi. She graduated from an all-Black high school at only 14, aspiring for better education that would prepare her for medical school. As such, she relocated to Harlem and enrolled at the prestigious Wadleigh High School for Girls, where she excelled as one of the only Black students. With top academic prizes in Latin and Greek, she gained admission under full scholarship to Cornell University’s pre-med program in 1932. Yet, she was prohibited from living in the campus dormitories due to her race. As a result, she worked in White faculty members’ homes as a live-in maid in exchange for a room in the attic.

At Cornell, Lawrence graduated as the only Black student in her class with nearly perfect grades. Despite her accomplishments, she still faced racism. Strangers regularly mistook her for a cleaner, rather than a student. She was often presumed to be illiterate. Sometimes, bias came from faculty members themselves; she recalls one professor, in an attempt to compliment her work ethic, had said, “Margaret, you don’t even seem like a Negro — you fit in so well.” Lawrence was also rejected from Cornell’s medical school, with the dean’s sole reasoning being that twenty five years ago, an admitted Black man failed to graduate as he had contracted tuberculosis and died. She was also denied an internship at the Babies Hospital, now known as the New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, due to her gender and race.

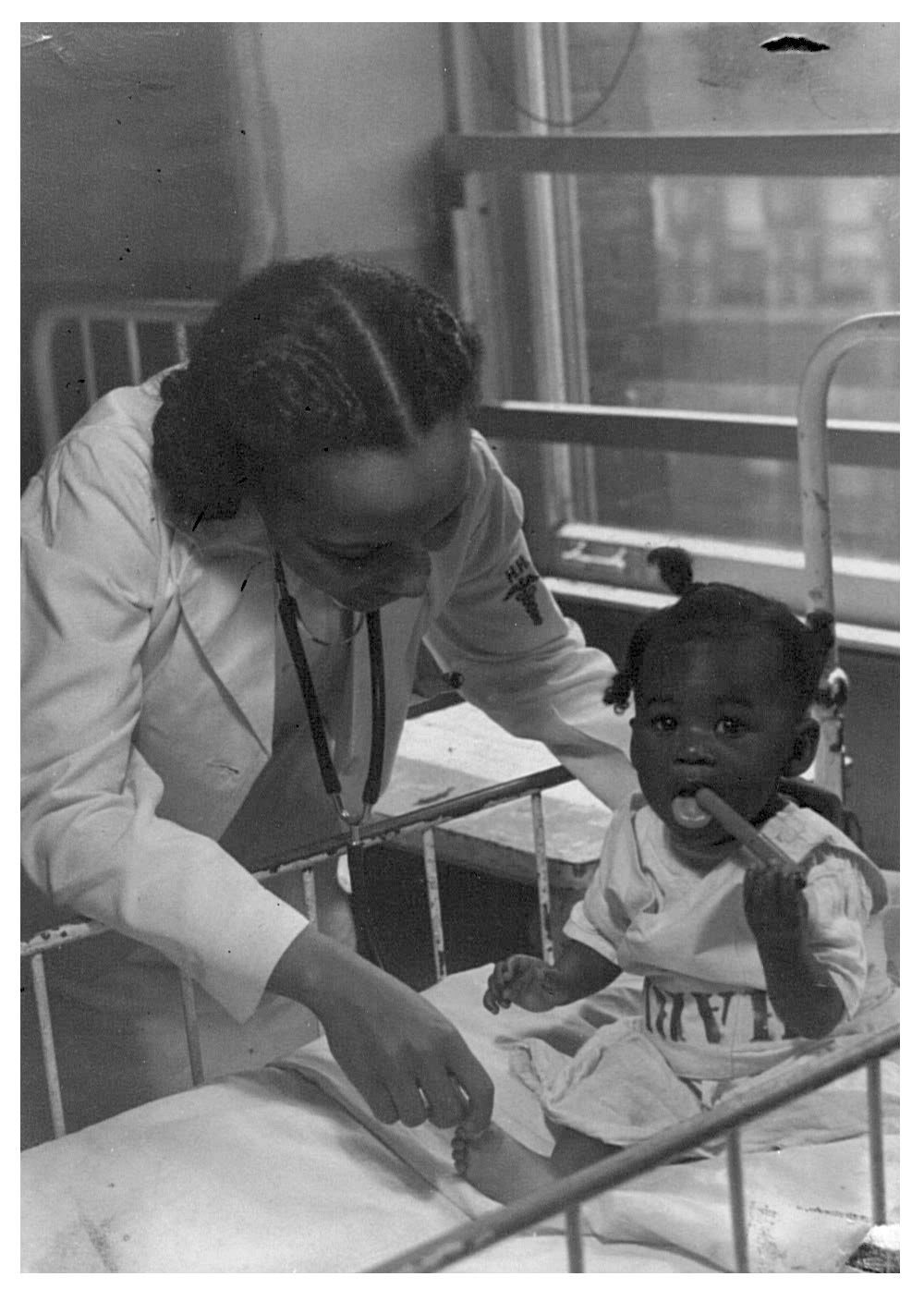

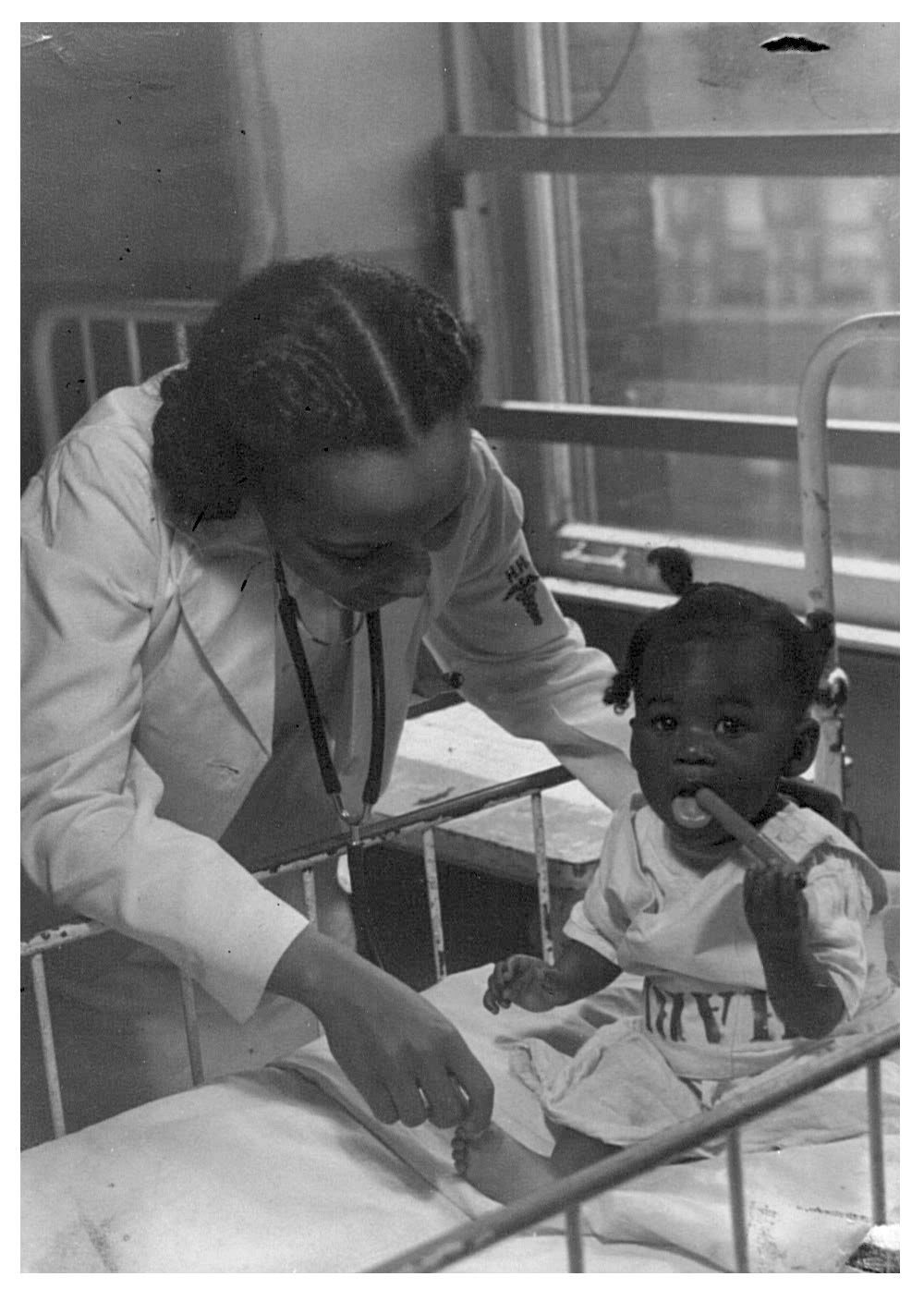

Devastated, Lawrence continued to persevere. Later armed with a Rosenwald Foundation Fellowship, she was accepted as the only Black woman in the class of 104 at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, under the condition that she would allow White patients at the university’s hospital to refuse her care (although this never actually occurred). Under Dr. Benjamin Spock, she learned about the intertwining forces of one’s physical, social, and psychological wellbeing, and in 1943 she graduated with a Master of Public Health. Her subsequent research drew inspiration from Spock’s multidimensional approach when researching the impact of the community, family and society on children’s physical and mental health. According to her daughter, “It was Spock who gave [Lawrence] the first firm feeling of being a pediatrician and a child psychiatrist.” This perspective was also informed by an internship at Harlem Hospital during her postgraduate years, where she observed the detrimental impact of poverty and racism, and realized that effective medicine necessitated a systematic approach by fighting against oppression.

From 1943 to 1946, she began to teach pediatrics and public health at Meharry Medical College and started a National Research Counsel fellowship a year later at the Babies Hospital. With the help of her mentor Dr. Viola Bernard, a professor emeritus in psychiatry at Columbia, she was admitted as the first Black student at the university’s Psychoanalytic Center and became certified in 1948. In the same year, she was also the first Black American to complete residency at the New York Psychiatric Institute. Five years later, she became the first Black child psychiatrist and begun practicing in Rockland County, NY. Lawrence was also the first to develop several therapy programs in elementary schools, hospital clinics (such as the the Rockland County Community Centre for Mental Health), and daycares. She also helped found the Harlem Family Institute, a low-fee parent-child counseling centre that services the Harlem school community.

She focused her research on children’s mental health and led a prolific career, writing several articles and two influential books. In the 1950s, she collaborated with Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark to assist with their famous research on the negative impacts of segregated schooling. Lawrence helped lead the movement which pushed for school psychologists to support student’s emotional wellbeing. She also extensively researched the mental health of children from low-income metropolitan neighborhoods, documenting poverty’s role as a major stressor. During her sabattical in the 1970s, her research compared mental health similarities in children from East and West Africa as well as rural Georgia and Mississippi.

For twenty one years, Lawrence was the chief of Harlem Hospital’s Developmental Psychiatric Service for Infants and Children. In her time here, she developed its Therapeutic Nursery, its Division of Child Psychiatry, and its Developmental Psychiatry Centre for Infants, Young Children, and their Families. She simultaneously tended to a faculty position in the psychiatric department at Columbia University until 1984, after which she retired from both positions and began her own private practice.

In recognition of her contributions, Yale University awarded Lawrence with an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 1998, and Swarthmore College presented Lawrence with an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 2003. She has also won a number of prestigious awards, such as the J.R. Bernstein Mental Health Award, Outstanding Women Practitioners in Medicine Award, Episcopal Peace Fellowship’s Sayre Prize, amongst several others.

Lawrence is survived by her three children, whom she raised with her late sociologist and activist husband, Charles Radford Lawrence II. Dr. Margaret Lawrence was an example of determination, resilience, and excellency. Breaking numerous racial barriers, Lawrence became a renowned pediatrician, child psychiatrist, and the world’s first Black psychoanalyst. An inspiration for generations to come, Lawrence’s passion for healing, children, and activism invigorated social justice awareness within psychotherapy.

By Lucy Xie (2020)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Lawrence, Margaret Morgan (1971). The mental health team in the schools. New York, NY: Behavioral Publications.

Lawrence, Margaret Morgan (1975). Young inner city families: Development of ego strength under stress. New York, NY: Human Sciences Press.

Lawrence, M. M. (1982). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy among poverty populations and the therapist's use of the self. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 10(2), 241-255.

Lawrence, M. M., Spanier, I. J., & Dubowy, M. W. (1962). An analysis of the work of the school mental health unit of a community mental health board. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 32(1), 99.

Lawrence, M. M. (1956). A comprehensive approach to the study of a case of familial dysautonomia. Psychoanalytic Review, 43(3), 358-372.

About Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Carey, C.W. (2008). "Lawrence, Margaret Morgan". In Johnson, G. J. (Ed.), African Americans in Science: An Encyclopedia of People and Progress (pp. 142-144). Reference Reviews.

Lightfoot, S. L. (1988). Balm in Gilead: Journey of a healer. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Warren, W. (1999). Black women scientists in the United States. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Photo Gallery

Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Birth:

1914

Death:

2019

Training Location(s):

PhD, Swarthmore College (Honorary) (2003)

PhD, Yale University (Honorary) (1998)

Cert., Columbia Psychoanalytic Center (1948)

MA, Columbia University (1943)

BA, Cornell University (1938)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Meharry Medical College (1943-1946)

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (1963-1984)

Other Media:

Media Links

Changing the Face of Medicine Profile

The Fellowship of Reconciliation Profile

Awards and Recognitions

Swarthmore College Honorary Degree Citation

Obituaries and Tributes

Wall Street Journal tribute by daughter Sara Lawrence Lightfoot

Career Focus:

Psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, clinical psychology, psychiatry, children’s mental health

Biography

On August 19, 1914, Margaret Cornelia Morgan Lawrence was born in Harlem, New York to an Episcopal priest father and an elementary school teacher mother. Although her parents lived in Richmond, Virginia, they temporarily relocated to Harlem for her birth; their first son had died in 1912 from cogenital conditions in the local segregated hospital, and they believed the healthcare received up north would be better than in the Jim Crow south. Despite the virulence of racial discrimination, Lawrence shined from a young age, and had large ambitions to become a pediatric doctor to save children like her brother.

Lawrence grew up in the heavily segregated Vicksburg, Mississippi. She graduated from an all-Black high school at only 14, aspiring for better education that would prepare her for medical school. As such, she relocated to Harlem and enrolled at the prestigious Wadleigh High School for Girls, where she excelled as one of the only Black students. With top academic prizes in Latin and Greek, she gained admission under full scholarship to Cornell University’s pre-med program in 1932. Yet, she was prohibited from living in the campus dormitories due to her race. As a result, she worked in White faculty members’ homes as a live-in maid in exchange for a room in the attic.

At Cornell, Lawrence graduated as the only Black student in her class with nearly perfect grades. Despite her accomplishments, she still faced racism. Strangers regularly mistook her for a cleaner, rather than a student. She was often presumed to be illiterate. Sometimes, bias came from faculty members themselves; she recalls one professor, in an attempt to compliment her work ethic, had said, “Margaret, you don’t even seem like a Negro — you fit in so well.” Lawrence was also rejected from Cornell’s medical school, with the dean’s sole reasoning being that twenty five years ago, an admitted Black man failed to graduate as he had contracted tuberculosis and died. She was also denied an internship at the Babies Hospital, now known as the New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, due to her gender and race.

Devastated, Lawrence continued to persevere. Later armed with a Rosenwald Foundation Fellowship, she was accepted as the only Black woman in the class of 104 at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, under the condition that she would allow White patients at the university’s hospital to refuse her care (although this never actually occurred). Under Dr. Benjamin Spock, she learned about the intertwining forces of one’s physical, social, and psychological wellbeing, and in 1943 she graduated with a Master of Public Health. Her subsequent research drew inspiration from Spock’s multidimensional approach when researching the impact of the community, family and society on children’s physical and mental health. According to her daughter, “It was Spock who gave [Lawrence] the first firm feeling of being a pediatrician and a child psychiatrist.” This perspective was also informed by an internship at Harlem Hospital during her postgraduate years, where she observed the detrimental impact of poverty and racism, and realized that effective medicine necessitated a systematic approach by fighting against oppression.

From 1943 to 1946, she began to teach pediatrics and public health at Meharry Medical College and started a National Research Counsel fellowship a year later at the Babies Hospital. With the help of her mentor Dr. Viola Bernard, a professor emeritus in psychiatry at Columbia, she was admitted as the first Black student at the university’s Psychoanalytic Center and became certified in 1948. In the same year, she was also the first Black American to complete residency at the New York Psychiatric Institute. Five years later, she became the first Black child psychiatrist and begun practicing in Rockland County, NY. Lawrence was also the first to develop several therapy programs in elementary schools, hospital clinics (such as the the Rockland County Community Centre for Mental Health), and daycares. She also helped found the Harlem Family Institute, a low-fee parent-child counseling centre that services the Harlem school community.

She focused her research on children’s mental health and led a prolific career, writing several articles and two influential books. In the 1950s, she collaborated with Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark to assist with their famous research on the negative impacts of segregated schooling. Lawrence helped lead the movement which pushed for school psychologists to support student’s emotional wellbeing. She also extensively researched the mental health of children from low-income metropolitan neighborhoods, documenting poverty’s role as a major stressor. During her sabattical in the 1970s, her research compared mental health similarities in children from East and West Africa as well as rural Georgia and Mississippi.

For twenty one years, Lawrence was the chief of Harlem Hospital’s Developmental Psychiatric Service for Infants and Children. In her time here, she developed its Therapeutic Nursery, its Division of Child Psychiatry, and its Developmental Psychiatry Centre for Infants, Young Children, and their Families. She simultaneously tended to a faculty position in the psychiatric department at Columbia University until 1984, after which she retired from both positions and began her own private practice.

In recognition of her contributions, Yale University awarded Lawrence with an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 1998, and Swarthmore College presented Lawrence with an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 2003. She has also won a number of prestigious awards, such as the J.R. Bernstein Mental Health Award, Outstanding Women Practitioners in Medicine Award, Episcopal Peace Fellowship’s Sayre Prize, amongst several others.

Lawrence is survived by her three children, whom she raised with her late sociologist and activist husband, Charles Radford Lawrence II. Dr. Margaret Lawrence was an example of determination, resilience, and excellency. Breaking numerous racial barriers, Lawrence became a renowned pediatrician, child psychiatrist, and the world’s first Black psychoanalyst. An inspiration for generations to come, Lawrence’s passion for healing, children, and activism invigorated social justice awareness within psychotherapy.

By Lucy Xie (2020)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Lawrence, Margaret Morgan (1971). The mental health team in the schools. New York, NY: Behavioral Publications.

Lawrence, Margaret Morgan (1975). Young inner city families: Development of ego strength under stress. New York, NY: Human Sciences Press.

Lawrence, M. M. (1982). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy among poverty populations and the therapist's use of the self. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 10(2), 241-255.

Lawrence, M. M., Spanier, I. J., & Dubowy, M. W. (1962). An analysis of the work of the school mental health unit of a community mental health board. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 32(1), 99.

Lawrence, M. M. (1956). A comprehensive approach to the study of a case of familial dysautonomia. Psychoanalytic Review, 43(3), 358-372.

About Margaret Morgan Lawrence

Carey, C.W. (2008). "Lawrence, Margaret Morgan". In Johnson, G. J. (Ed.), African Americans in Science: An Encyclopedia of People and Progress (pp. 142-144). Reference Reviews.

Lightfoot, S. L. (1988). Balm in Gilead: Journey of a healer. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Warren, W. (1999). Black women scientists in the United States. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.