Profile

Mary Parlee

Birth:

1943

Death:

2018

Training Location(s):

PhD, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1969)

BA, Radcliffe College (1965)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1994-2018)

The Graduate Center, City University of New York (1979-1993)

Barnard College, Columbia University (1975-1978)

Wellesley College (1969-1972)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Other Media:

Obituaries

Archival Collection

Mary Brown Parlee Papers, Archives of the History of American Psychology

Career Focus:

Feminist analyses of gender, bodies, embodiment; psychology of women/gender; psychology of menstruation, pregnancy, menopause; social construction of PMS; feminist science studies.

Biography

Mary Esther Brown Parlee was born in Oak Park, Illinois on February 11th, 1943. She recalled becoming interested in psychology in high school in the course of reading about the biochemistry of stress. This led her to focus on the biological and physiological bases of behavior as an undergraduate, even though she undertook her studies during the height of academic interest in psychoanalysis. She enrolled in Radcliffe College at Harvard University and received her bachelor’s degree in Biology in 1965, also completing the requirements for a psychology degree. As a result of majoring in biology, Parlee primarily had male colleagues and friends, and reported missing out on having female friendships. Regardless, she thoroughly enjoyed her time at Radcliffe and the scientific education she received there. Specifically, she took a keen interest in Brendan Maher’s course on the psychosomatic basis of behaviour pathology. Charlie Gross, who had taught physiological psychology at Harvard while Parlee was a student there, recommended the Ph. D. program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to her. Parlee then undertook her Ph. D. in experimental psychology with a minor in linguistics, working with Peter Schiller, Whitman Richards, and Dick Held.

Parlee focused her dissertation research on determining whether the underlying mechanism for locating an object in space is separable from the mechanism for form figure analysis. Though the overall graduate student population at MIT was only about 3% women at that time, her department, surprisingly, had an approximately even ratio of women to men. When she completed her degree in 1969, her thesis supervisor suggested that she should teach at nearby Wellesley, a women’s college, and remarked that it was the best she could do as a woman. By contrast, her male peers were asked what part of the country they would like to live in, and the department chair would get them jobs at appropriate universities with one phone call.

This was not the first overt sex discrimination Parlee experienced at MIT. On another occasion, a male graduate student told her to read an article in the New York Times titled ‘Doctor Asserts Women Unfit for Top Jobs Because of Raging Hormones,’ perhaps seeding her future interest in female physiology. Parlee did eventually work at Wellesley as an assistant professor in Psychology from 1969 to 1972, where she taught a course on the psychology of sex differences and a course on the history and systems of psychology. However, the teaching-intensive nature of this position was not a good fit. The combination of an unsatisfying experience at Wellesley and her involvement in a women’s group raised Parlee’s feminist consciousness. She decided that she wanted to find a way to connect her feminism with her work.

In 1972, Parlee left Wellesley and moved to South Carolina. Her then-husband, who worked as a radiologist, was assigned a job there and they had just had a daughter. Parlee obtained a position as a research associate at the Social Problems Research Institute at the University of South Carolina. At that time, she had already been awarded a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHHD) grant and was examining the significance of menstruation for adolescent females. As part of her research, Parlee had also begun reviewing literature on what was beginning to be called premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Parlee was strongly against calling premenstrual changes a “syndrome” since there was no sound evidence supporting its labeling as a syndrome. She was also wary of the attention that PMS was receiving from the medical community and drug companies. Finally, she was concerned that the emergence of PMS could have a detrimental impact on women’s likelihood of success in court cases and custody battles.

Coming from a biology background, she was outraged that biology might be used to justify discrimination against women. With Ellen Zimmerman, a student at Wellesley, Parlee wrote an article called “Behavioural changes associated with the menstrual cycle” and sent it to Psychological Bulletin. The reviewers gave them the feedback that the article was inaccurate and too negative. The editor even removed the quotation marks Parlee had deliberately placed around “premenstrual syndrome” throughout the article. Despite these challenges, Parlee did eventually publish the paper and received over 500 reprint requests, which she responded to personally and at her own expense. Understanding the impact that socially constructed views can have, Parlee transitioned into the sociology of science discipline and published an article in 1976 titled “Social factors in the psychology of menstruation, birth and menopause.”

In 1975, Parlee wrote the first review article on psychology of women, which appeared in the women’s studies journal Signs. In the article, she presented an overview and critique of the field of Psychology of Women. She provided compendiums of research studies on “psychology ‘of’ women”, “psychology against women” and “psychology for women”. Parlee emphasized the importance of examining women’s experiences and generating scientific understandings of human behavior that focused on women.

In 1977, she participated in the first conference on menstrual cycle research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. It was an important event not only in her career, but also for women-centered menstrual cycle research. She recalls being impressed by the number of accomplished women and the wide range of their research. She subsequently attended the second and third menstrual cycle research conferences and became immersed in an interdisciplinary group of feminist scholars and activists. She began considering how to expand the research findings beyond laboratory data and analysis. In 1991, Parlee went on her first sabbatical in 20 years at the University of York in England, which had a master’s program in Women’s Studies. She thoroughly enjoyed her time there, during which she read sociology and attended conferences on science studies and the history of science.

In 1979, Parlee became the Director of the Center for the Study of Women in Society at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, and a tenured professor in the developmental psychology subprogram. Parlee was also a visiting professor in Women’s Studies at Bowdoin College and Clark University.

Over the course of her career, Parlee took on institutional leadership roles such as president of Division 35, Psychology of Women of the American Psychological Association (1982-83). Overall, however, she found it more satisfying to pursue her interests independent of disciplinary or organizational constraints, and preferred to maintain her outsider status. In that way, she was able to cross disciplinary boundaries and maintain a critical stance towards psychology. She was a visiting professor at MIT in Women’s Studies starting in 1994.

Parlee strongly identified as an activist. Her interest in activism started through her volunteer work as an undergraduate student at the Metropolitan State Mental Hospital. Later, she also became involved with the Mental Patients’ Liberation Movement, which attempted to address clinical psychology and psychiatry’s roles in oppression.

Later in her career, Parlee was inspired when a transgender sociologist at Brandeis came to speak in her class. She attended several conferences on transgender research and found that although “transgender activists work together, as the term ‘community’ implies, to challenge pathologizing medical discourses and public intolerance, discrimination, violence and harassment,” there are still “political differences and alliances within the transgender community” as well as complex relations with other activists i.e. lesbian, gay or bisexual activists (1996, p. 632).

As a scientist, Parlee noted that feminism provided her with a wonderful community. She believed it was absolutely crucial to put women’s experience at the center of inquiry in order to nurture productive and fruitful perspectives. She also believed that the discrimination she experienced in academia was due at least in part to the subject matter she addressed, i.e., women’s health. Discrimination against feminist scholars still exists, as Parlee stated “In some circles, I am sure many circles still today, it is not an advantage to be identified as a feminist scholar.” Nonetheless, we are glad she did.

Mary Parlee passed away suddenly on June 27, 2018 at her home in Somerville, Massachusetts following a hemorrhagic stroke. She was in the midst of editing her interview transcript for this project when she died. Her daughter, Dr. Elizabeth Parlee, kindly retrieved the edited transcript and conveyed it to us. This is the version that we have included above.

By Grace Zhang Granofsky (2018)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Mary Brown Parlee

Parlee, M. B. (1973). The premenstrual syndrome. Psychological Bulletin, 80(6), 454-465.

Parlee, M. B. (1974). Stereotypic beliefs about menstruation: A methodological note on the Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire and some new data. Psychosomatic Medicine, 36(3), 229-240.

Parlee, M. B. (1975). Psychology. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1(1), 119-138.

Parlee, M. B. (1979). Psychology and women. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5(1), 121-133.

Parlee, M. B. (1981). Appropriate control groups in feminist research. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5(4), 637-644.

Parlee, M. B. (1982). Changes in moods and activation levels during the menstrual cycle in experimentally naive subjects. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 7(2), 119-131.

Parlee, M. B. (1984). Reproductive issues, including menopause. Women in midlife, 303-313.

Parlee, M. B. (1987). Media treatment of premenstrual syndrome. In Premenstrual syndrome (pp. 189-205). New York: Springer.

Parlee, M. B. (1991). Happy birth-day to Feminism & Psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 1(1), 39-48.

Parlee, M. B. (1996). Situated knowledges of personal embodiment: Transgender activists' and psychological theorists' perspectives on sex and gender. Theory & Psychology, 6(4), 625-645.

Zimmerman, E., & Parlee, M. B. (1973). Behavioral changes associated with the menstrual cycle: An experimental investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(4), 335-344.

About Mary Brown Parlee

Marecek, J. (2019). Mary Brown Parlee (1943–2018). American Psychologist, 74(5), 627.

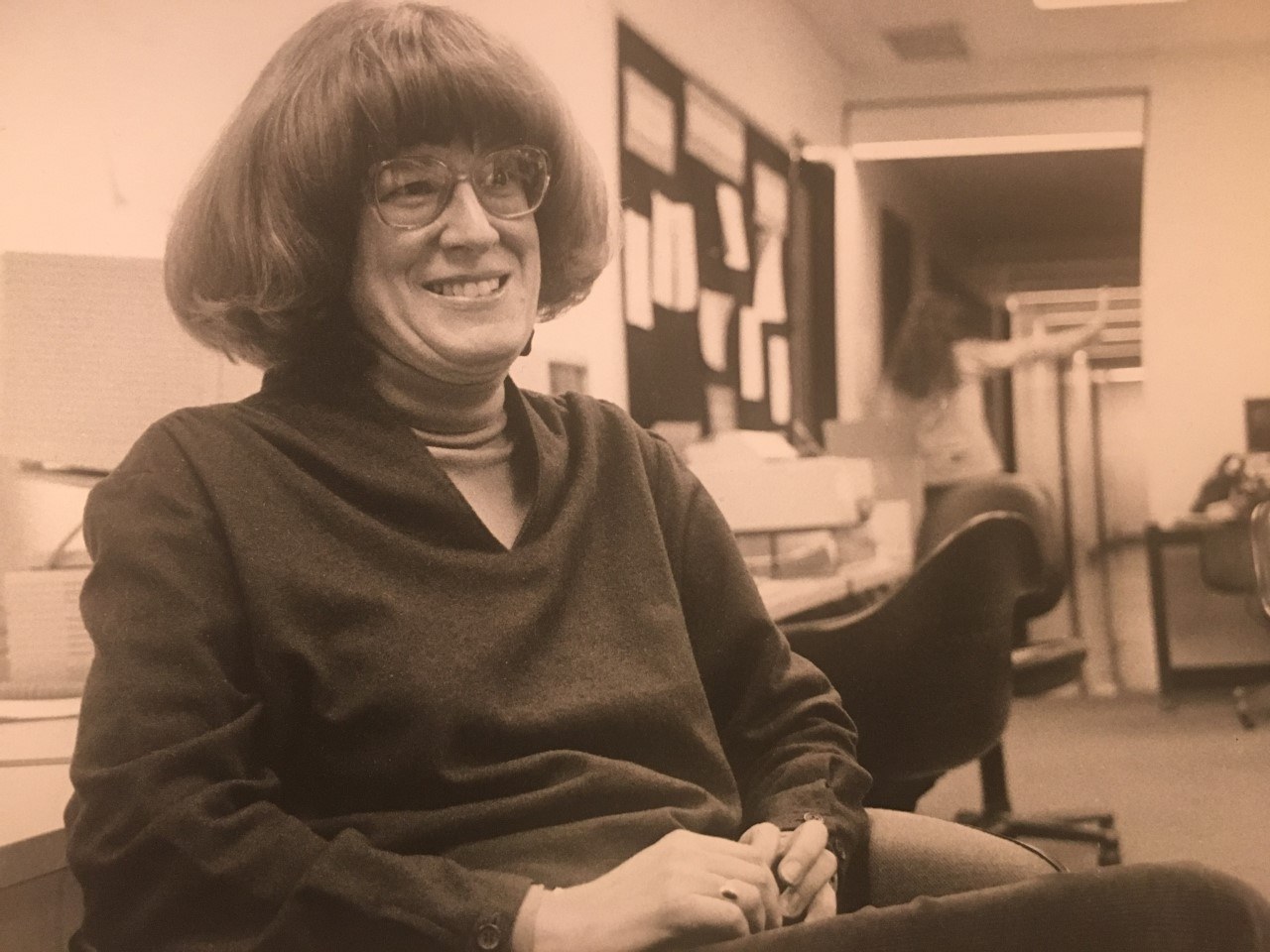

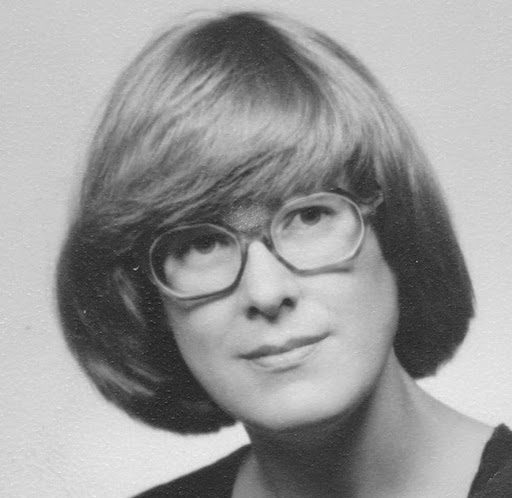

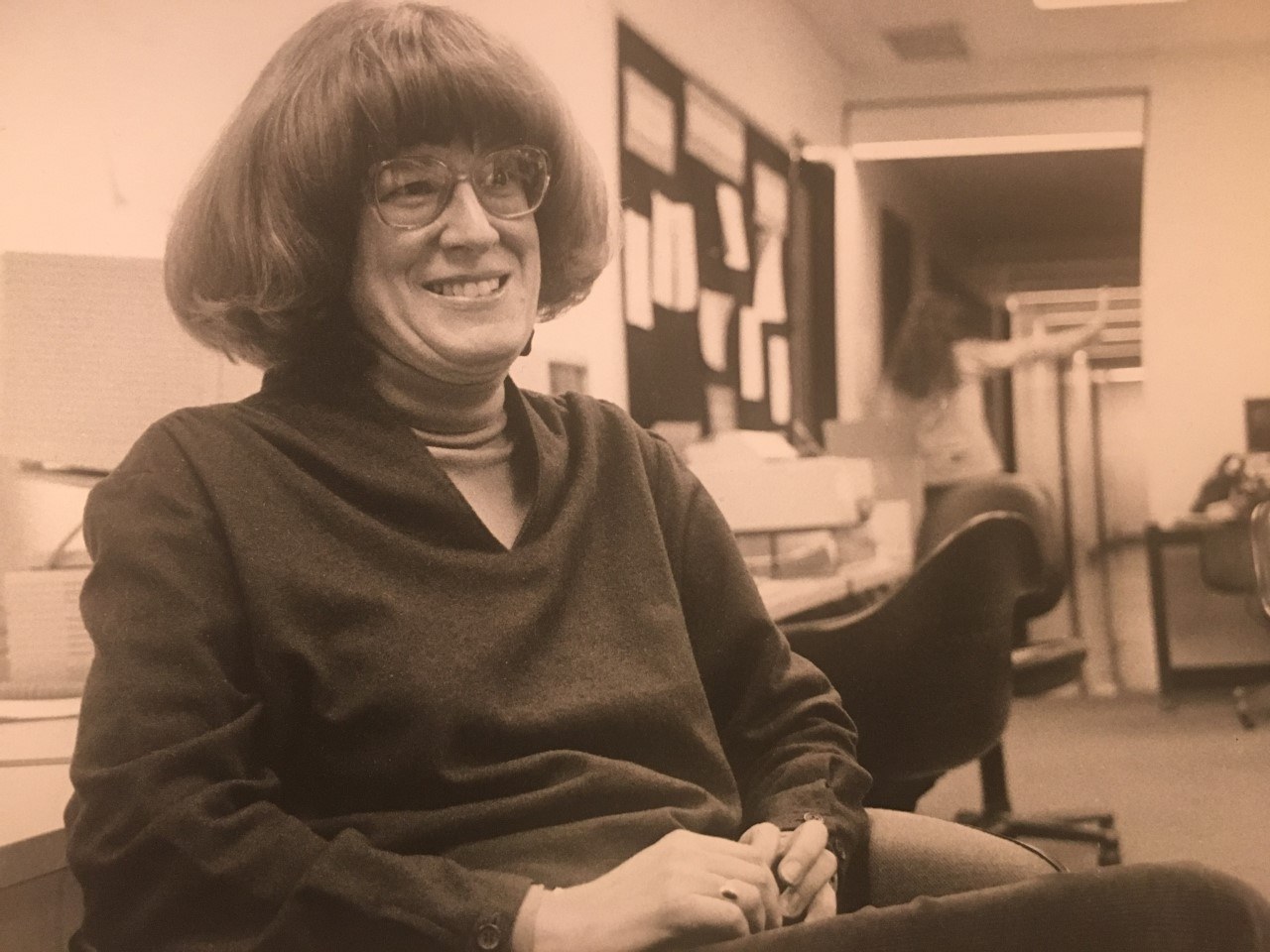

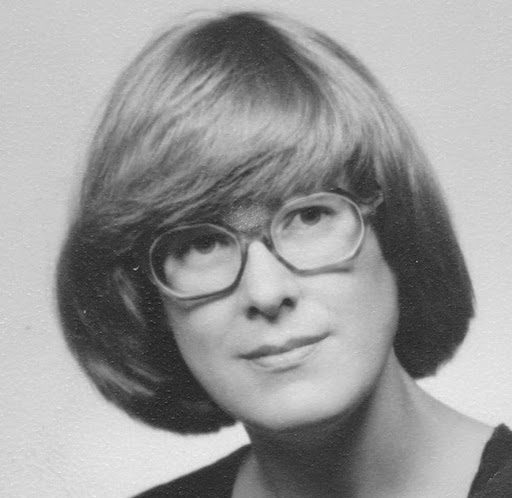

Photo Gallery

Mary Parlee

Birth:

1943

Death:

2018

Training Location(s):

PhD, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1969)

BA, Radcliffe College (1965)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1994-2018)

The Graduate Center, City University of New York (1979-1993)

Barnard College, Columbia University (1975-1978)

Wellesley College (1969-1972)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Other Media:

Obituaries

Archival Collection

Mary Brown Parlee Papers, Archives of the History of American Psychology

Career Focus:

Feminist analyses of gender, bodies, embodiment; psychology of women/gender; psychology of menstruation, pregnancy, menopause; social construction of PMS; feminist science studies.

Biography

Mary Esther Brown Parlee was born in Oak Park, Illinois on February 11th, 1943. She recalled becoming interested in psychology in high school in the course of reading about the biochemistry of stress. This led her to focus on the biological and physiological bases of behavior as an undergraduate, even though she undertook her studies during the height of academic interest in psychoanalysis. She enrolled in Radcliffe College at Harvard University and received her bachelor’s degree in Biology in 1965, also completing the requirements for a psychology degree. As a result of majoring in biology, Parlee primarily had male colleagues and friends, and reported missing out on having female friendships. Regardless, she thoroughly enjoyed her time at Radcliffe and the scientific education she received there. Specifically, she took a keen interest in Brendan Maher’s course on the psychosomatic basis of behaviour pathology. Charlie Gross, who had taught physiological psychology at Harvard while Parlee was a student there, recommended the Ph. D. program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to her. Parlee then undertook her Ph. D. in experimental psychology with a minor in linguistics, working with Peter Schiller, Whitman Richards, and Dick Held.

Parlee focused her dissertation research on determining whether the underlying mechanism for locating an object in space is separable from the mechanism for form figure analysis. Though the overall graduate student population at MIT was only about 3% women at that time, her department, surprisingly, had an approximately even ratio of women to men. When she completed her degree in 1969, her thesis supervisor suggested that she should teach at nearby Wellesley, a women’s college, and remarked that it was the best she could do as a woman. By contrast, her male peers were asked what part of the country they would like to live in, and the department chair would get them jobs at appropriate universities with one phone call.

This was not the first overt sex discrimination Parlee experienced at MIT. On another occasion, a male graduate student told her to read an article in the New York Times titled ‘Doctor Asserts Women Unfit for Top Jobs Because of Raging Hormones,’ perhaps seeding her future interest in female physiology. Parlee did eventually work at Wellesley as an assistant professor in Psychology from 1969 to 1972, where she taught a course on the psychology of sex differences and a course on the history and systems of psychology. However, the teaching-intensive nature of this position was not a good fit. The combination of an unsatisfying experience at Wellesley and her involvement in a women’s group raised Parlee’s feminist consciousness. She decided that she wanted to find a way to connect her feminism with her work.

In 1972, Parlee left Wellesley and moved to South Carolina. Her then-husband, who worked as a radiologist, was assigned a job there and they had just had a daughter. Parlee obtained a position as a research associate at the Social Problems Research Institute at the University of South Carolina. At that time, she had already been awarded a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHHD) grant and was examining the significance of menstruation for adolescent females. As part of her research, Parlee had also begun reviewing literature on what was beginning to be called premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Parlee was strongly against calling premenstrual changes a “syndrome” since there was no sound evidence supporting its labeling as a syndrome. She was also wary of the attention that PMS was receiving from the medical community and drug companies. Finally, she was concerned that the emergence of PMS could have a detrimental impact on women’s likelihood of success in court cases and custody battles.

Coming from a biology background, she was outraged that biology might be used to justify discrimination against women. With Ellen Zimmerman, a student at Wellesley, Parlee wrote an article called “Behavioural changes associated with the menstrual cycle” and sent it to Psychological Bulletin. The reviewers gave them the feedback that the article was inaccurate and too negative. The editor even removed the quotation marks Parlee had deliberately placed around “premenstrual syndrome” throughout the article. Despite these challenges, Parlee did eventually publish the paper and received over 500 reprint requests, which she responded to personally and at her own expense. Understanding the impact that socially constructed views can have, Parlee transitioned into the sociology of science discipline and published an article in 1976 titled “Social factors in the psychology of menstruation, birth and menopause.”

In 1975, Parlee wrote the first review article on psychology of women, which appeared in the women’s studies journal Signs. In the article, she presented an overview and critique of the field of Psychology of Women. She provided compendiums of research studies on “psychology ‘of’ women”, “psychology against women” and “psychology for women”. Parlee emphasized the importance of examining women’s experiences and generating scientific understandings of human behavior that focused on women.

In 1977, she participated in the first conference on menstrual cycle research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. It was an important event not only in her career, but also for women-centered menstrual cycle research. She recalls being impressed by the number of accomplished women and the wide range of their research. She subsequently attended the second and third menstrual cycle research conferences and became immersed in an interdisciplinary group of feminist scholars and activists. She began considering how to expand the research findings beyond laboratory data and analysis. In 1991, Parlee went on her first sabbatical in 20 years at the University of York in England, which had a master’s program in Women’s Studies. She thoroughly enjoyed her time there, during which she read sociology and attended conferences on science studies and the history of science.

In 1979, Parlee became the Director of the Center for the Study of Women in Society at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, and a tenured professor in the developmental psychology subprogram. Parlee was also a visiting professor in Women’s Studies at Bowdoin College and Clark University.

Over the course of her career, Parlee took on institutional leadership roles such as president of Division 35, Psychology of Women of the American Psychological Association (1982-83). Overall, however, she found it more satisfying to pursue her interests independent of disciplinary or organizational constraints, and preferred to maintain her outsider status. In that way, she was able to cross disciplinary boundaries and maintain a critical stance towards psychology. She was a visiting professor at MIT in Women’s Studies starting in 1994.

Parlee strongly identified as an activist. Her interest in activism started through her volunteer work as an undergraduate student at the Metropolitan State Mental Hospital. Later, she also became involved with the Mental Patients’ Liberation Movement, which attempted to address clinical psychology and psychiatry’s roles in oppression.

Later in her career, Parlee was inspired when a transgender sociologist at Brandeis came to speak in her class. She attended several conferences on transgender research and found that although “transgender activists work together, as the term ‘community’ implies, to challenge pathologizing medical discourses and public intolerance, discrimination, violence and harassment,” there are still “political differences and alliances within the transgender community” as well as complex relations with other activists i.e. lesbian, gay or bisexual activists (1996, p. 632).

As a scientist, Parlee noted that feminism provided her with a wonderful community. She believed it was absolutely crucial to put women’s experience at the center of inquiry in order to nurture productive and fruitful perspectives. She also believed that the discrimination she experienced in academia was due at least in part to the subject matter she addressed, i.e., women’s health. Discrimination against feminist scholars still exists, as Parlee stated “In some circles, I am sure many circles still today, it is not an advantage to be identified as a feminist scholar.” Nonetheless, we are glad she did.

Mary Parlee passed away suddenly on June 27, 2018 at her home in Somerville, Massachusetts following a hemorrhagic stroke. She was in the midst of editing her interview transcript for this project when she died. Her daughter, Dr. Elizabeth Parlee, kindly retrieved the edited transcript and conveyed it to us. This is the version that we have included above.

By Grace Zhang Granofsky (2018)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Mary Brown Parlee

Parlee, M. B. (1973). The premenstrual syndrome. Psychological Bulletin, 80(6), 454-465.

Parlee, M. B. (1974). Stereotypic beliefs about menstruation: A methodological note on the Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire and some new data. Psychosomatic Medicine, 36(3), 229-240.

Parlee, M. B. (1975). Psychology. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1(1), 119-138.

Parlee, M. B. (1979). Psychology and women. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5(1), 121-133.

Parlee, M. B. (1981). Appropriate control groups in feminist research. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5(4), 637-644.

Parlee, M. B. (1982). Changes in moods and activation levels during the menstrual cycle in experimentally naive subjects. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 7(2), 119-131.

Parlee, M. B. (1984). Reproductive issues, including menopause. Women in midlife, 303-313.

Parlee, M. B. (1987). Media treatment of premenstrual syndrome. In Premenstrual syndrome (pp. 189-205). New York: Springer.

Parlee, M. B. (1991). Happy birth-day to Feminism & Psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 1(1), 39-48.

Parlee, M. B. (1996). Situated knowledges of personal embodiment: Transgender activists' and psychological theorists' perspectives on sex and gender. Theory & Psychology, 6(4), 625-645.

Zimmerman, E., & Parlee, M. B. (1973). Behavioral changes associated with the menstrual cycle: An experimental investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(4), 335-344.

About Mary Brown Parlee

Marecek, J. (2019). Mary Brown Parlee (1943–2018). American Psychologist, 74(5), 627.