Profile

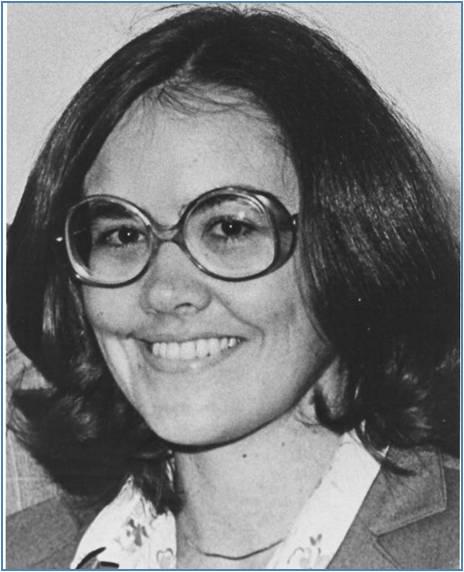

Nancy Felipe Russo

Birth:

1943

Training Location(s):

PhD, Cornell University (1970)

Primary Affiliation(s):

The American Institutes for Research

Richmond College, City University of New York

The American Psychological Association

Arizona State University (1985 - Present)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Career Focus:

Reproductive issues; sex roles and mental health; factors influencing women's educational and career achievements; ethnic minority women's issues; social identities.

Biography

I'm not complaining, I'm saying this has to change right now! It's not a complaint, it's an ultimatum!

-Nancy Russo

Although renowned for her groundbreaking work on women and psychology, Nancy Russo wasn't always a feminist. Raised in rural California, the granddaughter of Basque immigrants, Russo's father often said, "Nance, you can do anything you want! I'm behind you Nance!" Although she understood this kind of optimism in theory and though she would go on to become the first person in her family to earn an advanced degree, early in her career, Russo wasn't as likely to question some of the sexist conventions and practices common in academia, psychology, and married life in general.

In the 1960s and 70s, graduate and faculty positions for women were scarce. Where women were able to secure academic positions, they frequently faced overt discrimination and sexual harassment. Despite her highly competitive academic record, Russo was accepted to only one of the graduate schools to which she had applied. After completing her doctorate at Cornell in 1970, Russo followed her then husband to New York where he had been offered a job because"[that's what] good wives do."

As a graduate student, Russo came across a memo drafted by a male faculty member expressing his bitterness over the number of women at Cornell, asking, "What did women ever contribute to psychology anyways?" Russo recalls her indignant response, "I don't know, but I'm sure they did something!" And so she began researching women's many overlooked contributions to psychology. "I went and looked in these bibliographies and I found a ton of women! In fact, N. D Vernan was a woman! Zeigarnik was a woman! It was very exciting to find all these women!" For Russo, this event and the outrage she felt left a mark during a formative period in her career. Indeed, she went on to make substantial contributions in replacing women into the history of psychology.

Although Russo didn't have many female mentors, a few women did influence her early academic career, either personally or through their own work. Mary Prentice, one of Russo's instructors , frequently shared stories of a friend who was at Cornell where Russo eventually went on to do her graduate work: "I think she shaped my views a lot about where I could go and what I could do." Russo also credits feminist writers like Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer for their influence on how she came to connect psychology and feminism. "All the feminist writings were just eye-opening [and helped] to think about how psychology looked at women and understood women." Russo had a number of important male mentors as well. In particular, she credits her undergraduate thesis supervisor, Robert Sommer, whose strong support kept her on the path to a PhD and from whom she learned that psychology was useful for addressing social issues.

Russo's work on family planning and abortion issues has been highly influential. Her earliest explorations of these issues were carried out at the American Institutes for Research (AIR) where Russo received her first job. Her experiences at AIR emphasized the connections between family planning and women's status. In later research, Russo delved deeper into the links among unwanted pregnancy, violence, poverty, and self-esteem. Based on her research findings, Russo has stressed the need for more attention to be focused on issues around unwanted pregnancy: "There's too much concern about abortion and not enough attention given to the fact that women are having these multiple unwanted pregnancies." Of course, researching issues as contentious as abortion has not been easy and Russo notes that she has been attacked for engaging with the subject, sometimes finding photographs of foetus heads in her mailbox.

Throughout her career, Russo has been active in policy work. Indeed, Russo is renowned for her ability to make use of research findings to shape public policy. In her tenure with the American Psychological Association during the 1970s and 80s, Russo held a number of different positions from which she engaged with policy issues, including liaison to the Committee on Women, Affirmative Action Officer, and as the first director of the Women's Program Office. She was involved in revising ethical guidelines, drafting reports on the status of women in psychology, as well as contributing to the Health Systems Act, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

In 1977, Russo was appointed to the sub-panel on the Mental Health of Women of the President's Commission on Mental Health, although the panel's recommendations were promptly swept under the rug with the change in administration. "We have this subpanel and this report. We do a special issue on sex roles, equality and mental health in The Professional Psychologist.We're doing all this and [President Carter] doesn't win the election, so what do you do? Women's mental health is now old news..." In fact, the new women's mental health research agenda developed by Russo and her colleagues in response to the shift would result in groundbreaking change in terms of how issues of women's mental health were defined and addressed. They persuaded the National Institute of Mental Health to adopt their research agenda which later served as a model for shaping the national women's health agenda.

In 1985, Russo accepted a position at Arizona State University where she served as the Director of Women's Studies for eight years, going on to teach full time in the psychology department. Russo is known for being a highly engaging, committed, and effective teacher. She goes to great lengths to learn all of her students names and ensures that her courses are accessible and flexible enough to accommodate a variety of different needs and life situations: "I always teach a night class, because I want people who work to have access to a full range of classes. A lot of my students work, so I try to design the assignments so they can make up class work if they have to miss a class."

Russo has had to contend with significant personal denigration because of her work on women's reproductive rights. The recognition that you will never please everyone has been of central importance in facing this level of hostility. "You have to figure out who you value and who's important to you and make sure they keep you on track." One of the people Russo credits with keeping her on track is her husband, Allen Meyer (see image 4, below). Russo's first marriage ended in the early seventies. While Russo had followed her first husband from city to city according to his career opportunities, her second marriage has been different. When Russo moved to Arizona, Meyer quit his job at the Office of Management and Budget and followed her. Before this, when the couple commuted to work together and Russo was working long hours, they would eat dinner together in Russo's office and Meyer would spend the rest of the evening reading on her couch until she was ready to go home. "I was very fortunate. My husband, Allen Meyer, has always supported me. He helps me do everything. He reads my stuff, he's a partner, and I help him too. We just have a great life and I get a lot of meaning from my work and I think he gets a lot of meaning from mine."

Indeed Russo's work, her research, her teaching, and her influence on policy has had tremendous meaning for countless numbers of women and men.

by Kate Sheese (2010)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Landrine, H. & Russo, N. F. (2009). Handbook of diversity in feminist psychology. New York: Springer.

Koss, M. P., Goodman, L. A., Browne, A., Fitzgerald, L., Keita, G. P., & Russo, N. F. (1994). No safe haven: Male violence against women at home, at work, and in the community. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Denious, J., & Russo, N. F. (2005). Controlling birth: Science, politics, and public policy. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 181-191.

Russo, N. F., & Denious, J. E. (2001). Violence in the lives of women having abortions: Implications for public policy and practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32, 142-150.

Kite, M. E., Russo, N. F., Brehm, S. S., et al. (2001). Women psychologists in academe: Mixed progress, unwarranted complacency. American Psychologist, 56, 1080-1098.

Ramos Lira, L., Koss, M. P., & Russo, N. F. (1999). Mexican-American women 's definitions of rape and sexual abuse. [Special Issue on Latinas]. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21(3), 236-265.

Major, B, Applebaum, M., Beckman, L., Dutton, M. A., Russo, N. F. & West, C. (2008). Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and abortion. American Psychological Association.

Photo Gallery

Nancy Felipe Russo

Birth:

1943

Training Location(s):

PhD, Cornell University (1970)

Primary Affiliation(s):

The American Institutes for Research

Richmond College, City University of New York

The American Psychological Association

Arizona State University (1985 - Present)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Career Focus:

Reproductive issues; sex roles and mental health; factors influencing women's educational and career achievements; ethnic minority women's issues; social identities.

Biography

I'm not complaining, I'm saying this has to change right now! It's not a complaint, it's an ultimatum!

-Nancy Russo

Although renowned for her groundbreaking work on women and psychology, Nancy Russo wasn't always a feminist. Raised in rural California, the granddaughter of Basque immigrants, Russo's father often said, "Nance, you can do anything you want! I'm behind you Nance!" Although she understood this kind of optimism in theory and though she would go on to become the first person in her family to earn an advanced degree, early in her career, Russo wasn't as likely to question some of the sexist conventions and practices common in academia, psychology, and married life in general.

In the 1960s and 70s, graduate and faculty positions for women were scarce. Where women were able to secure academic positions, they frequently faced overt discrimination and sexual harassment. Despite her highly competitive academic record, Russo was accepted to only one of the graduate schools to which she had applied. After completing her doctorate at Cornell in 1970, Russo followed her then husband to New York where he had been offered a job because"[that's what] good wives do."

As a graduate student, Russo came across a memo drafted by a male faculty member expressing his bitterness over the number of women at Cornell, asking, "What did women ever contribute to psychology anyways?" Russo recalls her indignant response, "I don't know, but I'm sure they did something!" And so she began researching women's many overlooked contributions to psychology. "I went and looked in these bibliographies and I found a ton of women! In fact, N. D Vernan was a woman! Zeigarnik was a woman! It was very exciting to find all these women!" For Russo, this event and the outrage she felt left a mark during a formative period in her career. Indeed, she went on to make substantial contributions in replacing women into the history of psychology.

Although Russo didn't have many female mentors, a few women did influence her early academic career, either personally or through their own work. Mary Prentice, one of Russo's instructors , frequently shared stories of a friend who was at Cornell where Russo eventually went on to do her graduate work: "I think she shaped my views a lot about where I could go and what I could do." Russo also credits feminist writers like Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer for their influence on how she came to connect psychology and feminism. "All the feminist writings were just eye-opening [and helped] to think about how psychology looked at women and understood women." Russo had a number of important male mentors as well. In particular, she credits her undergraduate thesis supervisor, Robert Sommer, whose strong support kept her on the path to a PhD and from whom she learned that psychology was useful for addressing social issues.

Russo's work on family planning and abortion issues has been highly influential. Her earliest explorations of these issues were carried out at the American Institutes for Research (AIR) where Russo received her first job. Her experiences at AIR emphasized the connections between family planning and women's status. In later research, Russo delved deeper into the links among unwanted pregnancy, violence, poverty, and self-esteem. Based on her research findings, Russo has stressed the need for more attention to be focused on issues around unwanted pregnancy: "There's too much concern about abortion and not enough attention given to the fact that women are having these multiple unwanted pregnancies." Of course, researching issues as contentious as abortion has not been easy and Russo notes that she has been attacked for engaging with the subject, sometimes finding photographs of foetus heads in her mailbox.

Throughout her career, Russo has been active in policy work. Indeed, Russo is renowned for her ability to make use of research findings to shape public policy. In her tenure with the American Psychological Association during the 1970s and 80s, Russo held a number of different positions from which she engaged with policy issues, including liaison to the Committee on Women, Affirmative Action Officer, and as the first director of the Women's Program Office. She was involved in revising ethical guidelines, drafting reports on the status of women in psychology, as well as contributing to the Health Systems Act, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

In 1977, Russo was appointed to the sub-panel on the Mental Health of Women of the President's Commission on Mental Health, although the panel's recommendations were promptly swept under the rug with the change in administration. "We have this subpanel and this report. We do a special issue on sex roles, equality and mental health in The Professional Psychologist.We're doing all this and [President Carter] doesn't win the election, so what do you do? Women's mental health is now old news..." In fact, the new women's mental health research agenda developed by Russo and her colleagues in response to the shift would result in groundbreaking change in terms of how issues of women's mental health were defined and addressed. They persuaded the National Institute of Mental Health to adopt their research agenda which later served as a model for shaping the national women's health agenda.

In 1985, Russo accepted a position at Arizona State University where she served as the Director of Women's Studies for eight years, going on to teach full time in the psychology department. Russo is known for being a highly engaging, committed, and effective teacher. She goes to great lengths to learn all of her students names and ensures that her courses are accessible and flexible enough to accommodate a variety of different needs and life situations: "I always teach a night class, because I want people who work to have access to a full range of classes. A lot of my students work, so I try to design the assignments so they can make up class work if they have to miss a class."

Russo has had to contend with significant personal denigration because of her work on women's reproductive rights. The recognition that you will never please everyone has been of central importance in facing this level of hostility. "You have to figure out who you value and who's important to you and make sure they keep you on track." One of the people Russo credits with keeping her on track is her husband, Allen Meyer (see image 4, below). Russo's first marriage ended in the early seventies. While Russo had followed her first husband from city to city according to his career opportunities, her second marriage has been different. When Russo moved to Arizona, Meyer quit his job at the Office of Management and Budget and followed her. Before this, when the couple commuted to work together and Russo was working long hours, they would eat dinner together in Russo's office and Meyer would spend the rest of the evening reading on her couch until she was ready to go home. "I was very fortunate. My husband, Allen Meyer, has always supported me. He helps me do everything. He reads my stuff, he's a partner, and I help him too. We just have a great life and I get a lot of meaning from my work and I think he gets a lot of meaning from mine."

Indeed Russo's work, her research, her teaching, and her influence on policy has had tremendous meaning for countless numbers of women and men.

by Kate Sheese (2010)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Landrine, H. & Russo, N. F. (2009). Handbook of diversity in feminist psychology. New York: Springer.

Koss, M. P., Goodman, L. A., Browne, A., Fitzgerald, L., Keita, G. P., & Russo, N. F. (1994). No safe haven: Male violence against women at home, at work, and in the community. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Denious, J., & Russo, N. F. (2005). Controlling birth: Science, politics, and public policy. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 181-191.

Russo, N. F., & Denious, J. E. (2001). Violence in the lives of women having abortions: Implications for public policy and practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32, 142-150.

Kite, M. E., Russo, N. F., Brehm, S. S., et al. (2001). Women psychologists in academe: Mixed progress, unwarranted complacency. American Psychologist, 56, 1080-1098.

Ramos Lira, L., Koss, M. P., & Russo, N. F. (1999). Mexican-American women 's definitions of rape and sexual abuse. [Special Issue on Latinas]. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 21(3), 236-265.

Major, B, Applebaum, M., Beckman, L., Dutton, M. A., Russo, N. F. & West, C. (2008). Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and abortion. American Psychological Association.